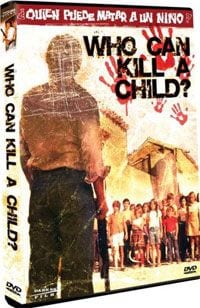

At last on American DVD in complete form, this remarkable movie embodies many trends in ’70s horror and Spanish cinema, subverting some while taking others to their logical extreme.

Who Can Kill a Child? is about a pair of young, dumb, skinny British tourists in Spain. Mustached Tom (Lewis Fiander) has a grimly ’70s look about him, put-upon yet pugnacious, a would-be alpha male who’s not sure he can cut the mustard. He patronises his wife Evelyn (Prunella Ransome), who is more winsome and flower-childish with her long blonde hair, not to mention the pregnancy vibe she’s got going.

She’s far enough advanced that it seems a bit late to be tramping around on holiday, but that’s believable for middle-class Brits who must take their holiday at the designated month and follow the flock of their fellow islanders to Spain. As a tourist, Tom naturally has pretensions of avoiding the normal touristy places. He wants to show Evelyn an unspoiled island he once visited, a place inhabited by a few hundred fisher folk. They must take a little motor-boat on a four-hour trip from the mainland; that’s worse than Gilligan’s three-hour cruise.

Before setting out, they ignore ominous signs, like a body washing up on shore. They turn aside from disturbing TV reports on the wars du jour, with one local merchant noting that children always suffer the most. This reminds the viewer that before we got to Tom and Evelyn in sunny Spain, we had to sit through the opening credits with footage and photographs of the Holocaust, the Vietnam War, and other terrible events, with a narrator emphasizing the numbers of children killed. This is profoundly non-entertaining, and many viewers may find it so disturbing as to question why it’s here, appended to a mere horror movie. Writer-director Narciso Ibanez Serrador is putting us on notice that what might seem like pulpy trash is an exploration of serious themes, that horror is metaphor, not escapism.

If this were a British film about Tom and Evelyn suffering nightmarish tortures at the hands of foreigners, it would merely be an exploration of xenophobia. But Spanish films about British tourists facing horror, for example Eugenio Martin’s A Candle for the Devil (1970), function as a critique of Spain’s traditional values vis a vis the local perception of liberated, immoral foreigners. This film goes beyond that and unites two different themes in horror cinema of the ’60s and early ’70s. In a bonus interview, cinematographer Jose Luis Alcaine declares that he sees the film as a cross between Night of the Living Dead and The Birds. Living Dead is certainly there, and reverberant in Franco-era Spanish horror, but the two main themes are “nature in revolt” and “evil children”.

The trope of “nature in revolt” dates to The Birds (1963) and flourished briefly in the early ’70s as various films laid an ecological guilt trip on the audience by implying — nay, coming out and saying — that the worm was turning, that the animal kingdom was paying humanity back for our sins against them, and that we deserve it for our thoughtless exploitation and greed. This is a “Mother Nature” variation on the apocalypse movies in which we bring about our own destruction through technological cleverness. Perhaps Living Dead can be seen as an extension of nature in revolt, if we regard the dead as part of nature.

The trope of “evil children” dates to Village of the Damned (1960), but picked up steam with Rosemary’s Baby (1968) through the Exorcist, Omen and It’s Alive cycles. This theme exploited the trendy notion of the Generation Gap, a phrase on the cover of so many magazines, and explained why kids these days were so dangerous to their elders, with their awful clothes and their rock ‘m’ roll (to quote a song from “Bye Bye Birdie”) and finally their free-loving, draft-dodging, freedom-marching, university-administration-building-commandeering ways. Clearly “they” were another species, visited upon responsible adults from outer space or the devil, something springing from our loins and nursed in our bosoms yet whose values were utterly alien to “us”.

These movies adopt the point of view of the horrified grown-ups against the child-monsters who must be destroyed — with the unexamined yet chillingly reductive logic of that. Note, however, that some of the sequels turn the idea on its head. Children of the Damned (1963) and the Alive sequels envision the children as misunderstood youths trying to defend themselves, a new species tjat must be protected against the adults who Just Don’t Understand. This raises an idea the other films leave as subtext: that our children are created to punish us for our sins.

And thus we have Who Can Kill a Child?. set on a mythical island but filmed seamlessly in several locations in bright broad daylight, with one scary night sequence as the couple ironically seek refuge in the jail. Locking themselves in a cell against an enemy that toys with them mercilessly, Tom and Evelyn finally confront what is inside them, emotionally and literally. Here the film extends to visions of horror that can still shock viewers, not because they’re graphic (they aren’t) but because they are rooted in shocking ideas.

Spanish horror films flourished in the waning years of fascist leader Francisco Franco, who died in 1975. The films are violent but prudish (because of the censor) and even explore that prudishness. Anti-Franco criticism wasn’t possible, but since political conservatism went hand-in-hand with the cultural conservatism of Catholic Spain, the latter could be served by films of extreme “punishment” that exploit and subvert the values in question through their destructive results. It’s painfully easy to read sexual repression in these movies as political repression.

A wonderful example of this is Serrador’s previous feature, La Residencia or The Finishing School or The House That Screamed from 1969 (not officially on US DVD). It’s set in the hothouse atmosphere of a girls’ school run by a severely repressed German woman who insists on order, to the detriment of her own offspring. Without ever mentioning Spanish history, it reminds us subtly that Franco was a political ally of Hitler.

That’s an example of how these films address children and young people as the primary victims of Spain’s social context. Another example is the greatest Spanish “horror” film of this era, Victor Erice’s hushed, sombre, claustrophobically beautiful Spirit of the Beehive (1973). That international art house hit played in the kind of theatres that never showed The House That Screamed. Anyway, films like this provide a generic context against which contemporary filmmaker Guillermo del Toro can more directly address the effect of Spain’s Civil War on children in The Devil’s Backbone and Pan’s Labyrinth.

In Who Can Kill a Child, Serrador broadens his social critique from the problems of Spain to the values of all warring humanity and makes the ultimate statement about the role of children in this genre. His films belong to a golden era of horror marked by pessimism and despair, when even the most minor films had the courage not to cop-out on their conclusions and without relying on tired “gotcha” endings.

By the way, this disc offers a choice of Spanish or English soundtracks. The correct choice is the English track, in which the two central British characters speak to each other in English and try to communicate with locals in fractured Spanish, while all Spaniards speak in Spanish only. This crucial nuance is lost in the Spanish dub.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)