“It doesn’t matter how small you are, as long as you have faith and a plan of action.” Julian Assange (Benedict Cumberbatch) asserts this admirable ethos to a rather stunned Daniel Domscheit-Berg (Daniel Brühl). Until this point, about a half hour into The Fifth Estate, Julian as suggested that he has squads of volunteers working for him, avid acolytes eager to help him to change the world. Now, Daniel realizes, it’s just Julian and him.

Daniel is duly flabbergasted by the news, and even pauses for a moment to wonder whether he should go forward with their world-changing project, that is, WikLleaks, Julian’s brainchild enhanced considerably by Daniel’s efforts over a few months. When Julian presents the lies he’s been telling as part of doing business, a means to an end of greater good, Daniel makes the decision to believe him, to have faith and to help to develop the plan of action, or at least to follow it as Julian lays it out, step by step.

These steps constitute the primary plot of The Fifth Estate, a fictionalized account of how Assange and his ever tiny band of cohorts made Wikileaks into an organization dedicated to exposing institutional secrets, that is, enacting “a whole new form of social justice.” The initial concept is at once small and immense, profound and simple, and as WikiLeaks takes it to increasingly larger institutions — corruptions in Kenya and the Swiss Bank Julius Baer — its reputation expands. Indeed, the film recounts, when Julius Baer sues WikiLeaks, the resulting publicity is good for the organization (more financial donations, more international media attention) and also complicating for Assange. For, the film contends, Julian is at least as interested in his own reputation and stardom as he is in the exposure of information.

It’s this last that becomes an issue for the film’s Daniel (the script is based on his book, Inside WikiLeaks, as well as WikiLeaks by David Leigh and Duke Harding), for as Julian’s celebrity increases, so it becomes apparent to Daniel that he’s something of an egotistical sort, with a sense of himself that is in no way small. This characterization will not be news to most viewers of the film, as this has been the story surrounded the real-life Assange, promulgated by both his enemies and friends, not to mention himself. But for Daniel, in particular, the revelation is not only slow in coming but also something of a moral lesson.

The growing tensions between the men are structured in two ways, one entirely conventional and the other visually tedious. For the first, the film provides Daniel with a new lens thorough which to view his partner — or, as Julian sees himself, his employer, though he pays his workers nothing — in the form of a girlfriend. Anke (Alicia Vikander) is encouraging of the project at first, but soon sees that Julian is a needy, self-absorbed, utterly insensitive bully, a point made manifest when Julian shows up one night at Daniel’s apartment, and takes no notice of Anke’s state of undress or that he’s interrupting the couple being a couple, essentially forcing Daniel to choose between them. When Daniel suggests that he must let Julian in because he has “nowhere else to go,” Anke announces that she does, and stomps off into the night, receding from Daniel’s view down a stairway that provides for echoing footsteps.

The question of just how extraordinary Julian’s social competitiveness may be compounded when he meets Daniel’s parents (Franziska Walser and Edgar), and against Daniel’s first instinct, comes to their home and acts out like a preteen, expressing his own anger about his missing or rejected or otherwise inept parents, and making clear for everyone — including Daniel — that perhaps his lofty activist goals don’t mean he must behave so cruelly toward others.

The film picks this up in the form or the US government’s resentments against WikiLeaks and Assange. Laura Linney plays a State Department diplomat whose personal associate (Alexander Siddig) is endangered by the WikiLeaks release of gunsight footage from a 12 July 2007 Baghdad airstrike, implicating the US in war crimes; that her job is also at stake because of Julian’s expanding “plan of action” allows the film to pose another set of questions, as to whether diplomatic careers can lead to “social justice” of any kind.

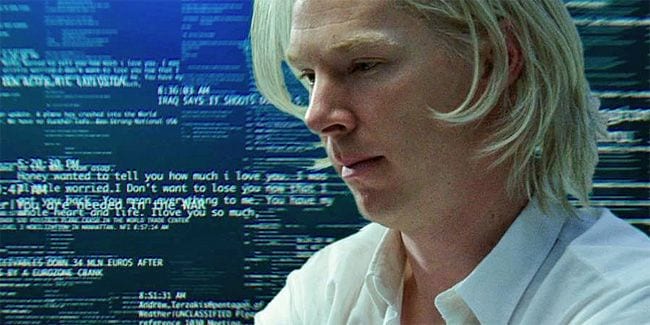

The Fifth Estate‘s second method of showing the mens’ relationship is less explicitly narrative contrivances, but rather, a visual solution to a narrative dilemma. As so much of their work occurs online, the film faces the usual problem of how to make screens and keystrokes compelling viewing. To solve this puzzle, Julian’s mind becomes something of a landscape for the film: as he works, the film shows an office-like space expanding forever, with a sandy floor and a blue sky as ceiling, desks and monitors stretching into the distance, occupied by many, many Julians.

Yes, h’s an egomaniac. Yes, he has visions quite beyond those of ordinary folks’ capacity. And yes, the movie is awfully corny in these too explanatory metaphorical efforts. The camera swoops and circles Julian at work, with close-ups of his face suggesting his consternation or pleasure. Simultaneously sensational and so banal, these images suggest the film’s disappointing lack of imagination in showing the interrelated constraints and immensities of how minds can do their work.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)