No dash, no flash, no flair, no flights of rhetorical fancy. No extra words. No wasted motion.

A Michael Connelly novel is a thing of cool beauty, meticulously plotted, rigorously controlled. Its angles are tight and sure. Nothing flops or wobbles. It always keeps its tie straight and its shirttail tucked in.

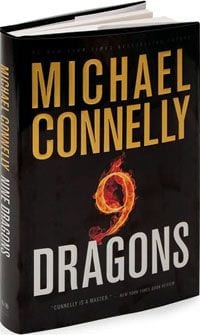

Nine Dragons is the latest Connelly novel to feature the author’s most famous creation, the stoic Los Angeles police detective Harry Bosch, a man whose emotional life was locked up in a long-term storage facility some time back. Bosch airs it out occasionally — he has been known to have a romantic fling here and there, and a few of his colleagues are sporadically deemed worthy of the term “friend” — but for the most part, the door is shut tight. The padlock is starting to show some rust.

In Nine Dragons, which includes a crucial scene in Hong Kong late in the book, Bosch’s crisp, cold-eyed rationality is blown to smithereens. Stoicism goes right out the window. And it is the vivid drama of this contrast — the destruction of Bosch’s neat, tight little world by the concussive heat of soul-ripping anguish — that gives the novel its ferocious energy, its mighty push.

Once under way, you can’t stop reading Nine Dragons and not just because you want to know whodunit. You want to know how Bosch is going to operate in a whole new kind of darkness.

It’s not the familiar darkness, the kind brought on by a realization of the depths of human depravity — that world, Bosch knows like the back of his hand — but the darkness caused by his complicity in bringing pain to people he cares about. “All roads led back to him,” Connelly writes of Bosch, as the ominous net of facts begins to tighten in the detective’s overheated brain, “and he wasn’t sure how he was going to live with it.”

To those who don’t know Bosch — and sales figures for Connelly’s novels suggest that they are rapidly becoming an endangered species — he was raised in an orphanage, served as a tunnel rat in Vietnam, loves jazz, hates hypocrisy, smokes but knows he shouldn’t. He has a teenage daughter named Madeline who lives with her mother in Hong Kong.

“It seemed to him,” Connelly writes, “that the weeks and months between seeing Maddie were getting more difficult. He missed her all the time.” Forget the flourishes, the ornate language: Bosch knows what he feels.

From the previous 14 novels that have chronicled Bosch’s crooked biography, readers have gleaned that he is almost always brave, often foolishly so. He can be infuriatingly self-righteous and exasperatingly judgmental. He holds a grudge.

He uses his intelligence and his intuition as often as his gun and his fists. He lives in an earthquake-damaged home with a small back deck; some evenings, Bosch heads out there and watches the lights of Los Angeles, while the music from a jazz CD unspools behind him, taking his thoughts by the hand and leading them slowly through a maze of narrow forking paths.

Nine Dragons opens with the proverbial bang. The owner of a liquor store in a marginal neighborhood is shot dead. Was it a random robbery or something else? Bosch and his partner get to work.

Among the deep, abiding pleasures of a Connelly novel is watching the competence of skilled craftsmen — both the author and his creation — as they do their jobs. Step by step, Bosch builds his case. Fingerprints, ballistics, pixels: Bosch is awash in the modern science that underlies the getting of the bad guys.

But this time, Bosch slips up. It’s just a small thing, a thing that shouldn’t matter. He takes a shortcut. One quick decision — and everything is set into motion. The darkness rushes in.

The plot of Nine Dragons is, like all of Connelly’s novels, machinelike in its ruthless, pristine efficiency. It may remind readers of the movie Taken (2008), in which Liam Neeson plays the avenging dad, but without the cartoonish violence. There’s plenty of violence in Nine Dragons, but it’s no cartoon.

What gives the novel its kick are not only the frenetic action scenes but also Bosch’s sorrow, his psychological self-impalement. To see a detective so adept at holding it together suddenly come apart, to see Bosch’s hard, straight-line world disintegrate into a mushy tangle, is to feel as shocked and adrift as he is.

If a hard-jawed cop with a lead-lined soul can be so swiftly undone by his grief, what’s next? If Bosch is this vulnerable, what chance do the rest of us have?

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)