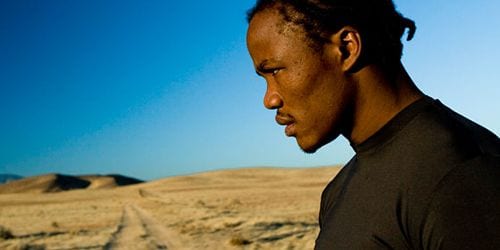

“He’s on the big stage because people know what he brings. He brings excitement.” As ESPN Sports writer Dan Rafael sees it, Kassim Ouma is a light middleweight boxing star because he hits hard. It helps too that he’s quick on his feet, photogenic, and visibly grateful for all the attention paid to him. As he first appears in Kassim the Dream, the young fighter is training in the desert, heat rising around and seemingly through him, so his figure blurs and warps. Cut to Cesar’s Palace in Vegas, 2004, where Kassim is fighting Verno Phillips for the IBF light middleweight title. Again, the story — of excitement, of aggression barely contained — inspires awe: “This man is a whirlwind in and out of the ring,” asserts the announcer. “You just hope he doesn’t spin out of control.”

This risk of excess might make Kassim “exciting.” But for him, the story is more complicated. As Kief Davidson’s documentary reveals, Kassim was born in Uganda and kidnapped at age six, then forced to serve as a child soldier for the National Resistance Army (NRA), led by Yoweri Museveni. “I did kill people,” he says, “I was like eight, just trying to follow orders.” When the rebels claimed victory in 1996, and the NRA became the national military, Kassim began boxing for the government, soon after defecting and earning Museveni’s official resentment. “I fight for the whole Uganda every time I step in the ring,” Kassim says. As the documentary begins, Kassim insists he bears no grudge for his traumatic childhood, though he’s prohibited from going home. All he wants to do, he says, is return to Uganda to visit his grandmother, whom he hasn’t seen in a decade. “She tells me the story of where my family come from,” he remembers.

In the States, Kassim is a gracious winner and dedicated athlete, training long hours and keeping faith with his manager Tom Moran. Though the film leaves out their specific shared history, the two men appear together throughout, with Kassim visiting Moran’s home for dinner and describing his deeply felt connection with his “black Irish” family, as Moran helps him through the diplomatic process to gain his pardon.

At the same time, the film underscores their differences. The Philadelphia-based Moran uses his avocation, painting, to take aim at American corruption and politics. “I’m a creative artist,” he explains. “I just started getting into political painting.” He dabs at his latest while he describes the hobbling figure in frame: “If George Bush went to war and came home with one leg and one arm, he might think twice about sending other people to war.” Kassim demurs, noting, “Where we’re from, we don’t have that freedom of speech.” As the camera turns to a picture of Bush on a leash, recalling the photo of Lynndie England at Abu Ghraib, Kassim points out, “In East Africa, if you did that, you are history. Nobody know where you went.” When he adds, “I ain’t got no problem with anybody,” then leaves the room, it’s unclear whether he’s uncomfortable with performing politics, or whether he actually believes what he’s saying. Moran nods, seeing the broader context: “There’s a lot of real dangers in Kassim going back to Africa, he says. “Because whether he likes it or not, Kassim is political.”

The film, available on Sundance Selects On-Demand through 23 February 2010, demonstrates how this ineluctable status shapes Kassim’s experience. While he trains, he’s also distracted by his efforts to be a good father to his two sons, a toddler in America and a nine-year-old, Umar, still in Uganda. With Moran’s help, Kassim and his mother, who lives with him in Pennsylvania, arrange for Umar to come stay with them, the film crew capturing the boy’s arrival at the airport, looking tired and shy after long hours traveling alone. It’s not long before Kassim has taken the boy shopping — flirting with the clerk so she’ll help them decide on outfits.

Kassim’s focus on family is both earnest and naïve, a set of ideals shaped by his own loss and yearning, as well as the fictions and ideals propagated in America. Moran serves as father, teacher, and big brother, on one hand urging him to forego late nights with friends before fights, and on another performing his own worry for the camera. Moran remembers, “One of the first things we really had a blowup was over weed,” a blowup he now understands as his own lesson learned. When Moran cautioned his fighter concerning drug tests and losing his boxing card, Kassim comes back with his reasons for such risk-taking: “Uncle Tom, you don’t understand. I’ve been smoking since I was seven years old, eight years old. How do you think a little boy copes with being in a war?” (The movie does not dig any more deeply into Kassim’s misbehaviors or legal troubles.)

As Moran describes this past confrontation, he voices the film’s premise, that Kassim’s experience is profoundly traumatic, and quite beyond language or containment. As the movie leaves behind boxing and Kassim’s new American life, it observes his journey home. The last section of Kassim the Dream suggests another way to think about “the dream,” as he remains haunted by his past. If he is no longer “a little boy,” Kassim continues to wrestle with the effects of the violence he witnessed and committed. When he visits with young Ugandans, now as he once was, soldier-boxers seeking release, order, and identity through this most brutal sport, the film shows eerie silhouettes, as they copy his movements and absorb his instructions.

His reunion with his grandmother is more immediately painful, as his visit to his father’s grave (Kassim narrates that his father was murdered when and because he escaped). Collapsing in tears as he names the guilt he feels for leaving them behind, Kassim exposes how hard his journey has been, from abject to brash, from broken to remade. The film cannot show precisely Kassim’s experience, the child’s unbearable pain borne and carried forward. Still, it makes visible the process of healing and hoping, the dream he pursues and embodies.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)