I realized that people don’t really care about what something is about sometimes, as long as it’s a good story. As long as it’s a good story, then they’ll make whatever meaning they need from it come out of it.

— Tennessee Jones, “Nebraska”

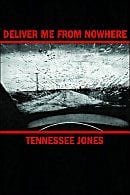

Tennessee Jones’ debut short-story collection, Deliver Me from Nowhere, is essentially a covers album in book form. Jones, who edits the zine Teenage Death Songs, has found inspiration in Bruce Springsteen’s 1982 album, Nebraska, and has written a story for each of the ten songs, borrowing titles, settings, characters, and themes. In a sense, this reinterpretation is entirely appropriate: Recorded on a four-track and reportedly inspired by John Steinbeck’s Depression-era novels, Nebraska is a decidedly bleak collection of story-songs whose sparseness of sound (Springsteen’s first without the E Street Band) feels darkly ominous. For a writer like Jones to cover the album closes the circle of influence — from writer to musician and back to writer.

Springsteen, however, could escape Steinbeck’s looming shadow because he wasn’t directly basing his songs on The Grapes of Wrath (even his 1995 album, The Ghost of Tom Joad, is more about the ideas the character represents rather than about the character himself). Unfortunately, Jones’s undertaking, which is both ambitious and somewhat foolish, is doomed from its conception: He has chosen to cover an album whose songs are already in narrative form, which threatens to render Deliver Me from Nowhere redundant. For the project to succeed, Jones has to justify rewriting the songs as short stories, and there’s the catch: when he does justify his stories, they tend to stray so far from familiar territory that they provoke unfavorable comparisons to the originals. When Jones fails to justify them, they become simply pointless, mere transcriptions from vinyl to paper.

Deliver Me from Nowhere begins where the album started: with “Nebraska,” which Springsteen wrote in the voice of real-life serial killer Charles Starkweather. Jones switches the point of view from the Starkweather character (here named George) to his teenage lover. But the story relies too heavily on Springsteen’s original, even as it relates slightly different events from the song, and the transgressive relationship between George and the unnamed narrator jumps from statutory to murderous with little build-up or explanation.

The narrator remains a cipher throughout, with Jones neglecting to show the motivations behind her actions, apparently deferring to Springsteen. She’s not especially bored or dreamy or impressionable or angry or mean or anything. In the end she can only offer this vague justification: “I know not everyone would have gone off with George the way I did, but I had to see what happened. I had to see what would open up inside of me.”

Jones has similar trouble with “Johnny 99,” which hews too closely to its source. But he fares only slightly better when he strays from Springsteen’s storylines and provides details to flesh out the originals. Perhaps the best story in the collection, “Mansion on the Hill” is based on one line from the song: “In the day you can see the children playing.” But out of this line Jones draws his best material as he moves from the song’s class delineations to a realization of gender differences among teenagers. It helps that his narrator is recalling events from her childhood and so has the perspective of age and experience.

“Atlantic City,” though, proves less successful. Jones jettisons the cheap neon atmosphere and the precariousness between hitting it big and losing it all; his “Atlantic City” is quieter, less fixated on the city’s tacit promise to eradicate one’s class standing with either a jackpot or mob connection. Frank and Eliza, who work as janitors at a factory, come to Atlantic City to gamble, with the intention of giving all their earnings to their daughter before committing a much direr act. They’ve decided long ago how the story will end, and as a result, “Atlantic City” feels fatally predetermined. There’s no precarious conflict here, just a drawn-out predicament that leads to its agreed-upon conclusion.

Jones’s piece tells a dramatically different tale than Springsteen’s song, but most of these stories simply elaborate upon the originals, filling in back stories and supplying details where the Boss’s minimalist approach gave none. In “Highway Patrolman,” the narrator is again a deputy, but with a different name and slightly different relationships with his wife and his wayward brother. Jones ruins the song’s heartbreaking simplicity by adding a story about malicious homophobia. The narrator’s defining conflict — he’s a law enforcer who has himself broken the law — becomes all too obvious. For Springsteen, it’s enough that the narrator is in such a difficult predicament with his brother, and his final act of watching those taillights disappear into the night evokes a morality as black and white as the photograph gracing the album cover.

As many musicians know, Springsteen has such an individual style — dense with words and romantic belief in the healing powers of rock and roll — that covering any of his songs proves exceedingly difficult, but not impossible. Julianna Baggott’s story “The Bodies of Boys,” based on Springsteen’s “Spirit in the Night” and published last year in the collection Lit Riffs, is the gold standard for literary covers of rock songs. She takes a minor character — Crazy Janey — and gave her a back-story and a conflict of her own, effectively freeing her from the Boss’s masculine voice. By contrast, Jones seems overly reverent: He borrows the songs’ meager details, bleak atmosphere, and populist outlook, but he never thinks to challenge, expand, or update them.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)