F. Scott Fitzgerald said that in American lives there are no second acts. He simply did not live long enough.

— Frank McCourt

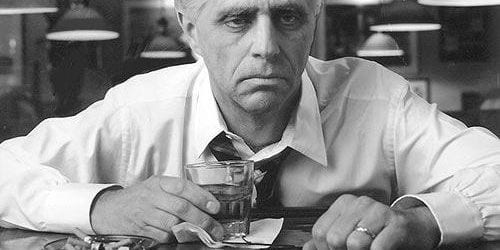

Seven years ago, I was in my mid-40s, senior VP and director of marketing for a Midwest subsidiary of one of the world’s largest financial institutions. I had a good salary, plenty of perks and yet I wasn’t very happy. If when I was an art student in the ’70s I’d been told that my future lie in being a suit (even a hip one), I would have either laughed or spit. Although it freaked out my boss, not to mention my parents, I quit my job to enroll in an advanced degree program at the New School for Social Research in New York City. (My wife was totally supportive even though it meant a seriously diminished lifestyle.) I’m still working on my dissertation and pretty much broke, but can’t imagine having sat in that corner office all this time, white-knuckling it in my Herman Miller padded-leather desk chair, sphincter constricted, wondering what would’ve happened if only I’d …

Most people don’t have the luxury of choosing to bail from a high-paying job to live the stressed-out, pizza-scarfing life of a grad student. More often than not, they get bounced out of positions they had planned to someday retire from. (Of the hundreds of people I worked with, only a fraction haven’t been downsized, synergized, merged, outsourced, or whatever euphemism you want to use, out the door at the company I left after 20-plus years.) The “lucky ones” are hanging on for dear life, usually doing the work two or three people once did, trying to bleed a few more years of decent pay and healthcare coverage before signing on at Wal-Mart to await their eligibility for Social Security and Medicare. Most aren’t ready psychologically and far more often aren’t set economically to stop working entirely. It’s another of those irritating trends we Baby Boomers are accused of always setting.

In Encore: Finding Work that Matters in the Second Half of Life, Marc Freedman gets a bead on the situation and offers a solution. We’re living longer and are generally healthier in our later years than our forebears, despite the loathsome state of American healthcare. Having been indoctrinated for decades into consumerism fueled by easy credit, we haven’t saved enough, nor with the decline of defined-benefit plans over the past quarter century, do we have enough pension coverage to sustain retirements that can now last for upwards of 25 years. At the same time, corporations are shedding older employees, slashing payroll and benefit costs, in pursuit of higher profit margins. In Freedman’s mind, this is creating a tremendous waste of human capital — legions of people are fit enough and have valuable experience but are too often sidelined into idleness or mind-numbing McJobs — that could be used to improve the American commonweal. Encore suggests that older workers have an opportunity to exchange money for meaning in their working lives and should be encouraged to do so.

Besides looking at American retirement policy, its background and prospects, Encore profiles people Freedman feels are part of the solution. There’s a woman who went from being a successful insurance agent to working on homelessness issues in the US Department of Housing and Urban Development. Another who had been a truant officer in the Detroit public schools is now a critical care nurse. A used car salesman from New Hampshire set up a nonprofit organization that helps low-income people get affordable financing to buy new fuel-efficient cars. And there are others, some of whom still work because they want to but most because they must. Either way, a big incentive is doing something that matters rather than simply drawing a paycheck. These examples are inspiring. Unfortunately, there are plenty of roadblocks to realizing Freedman’s vision.

As with so many progressive notions, the biggest impediment is the myopia of an outdated status quo. In this case, it’s the welfare capitalist model circa 1950. Part of the postwar social contract was to provide career paths for American workers that would maximize both production and consumption, providing a rising tide to lift all boats as the saying at the time went. Government would supply basic infrastructure and a modest social safety net and corporations, updating Gilded Age paternalism, would see to their own workers’ long-term welfare. Labor for its part agreed to cooperate with government and business to secure its place at the table. (An excellent telling of this story is Sanford M. Jacoby’s Modern Manors: Welfare Capitalism since the New Deal.) Part of the compact was to systematically ease older workers out of the way to make room for those coming in at entry level. Hence “the Golden Years” were invented to glamorize leisure as the fulfillment of the American Dream. The demographics of today’s America, with one quarter of the population slouching toward the golf course and threatening to hang around the clubhouse for decades, make this model untenable.

Other prejudices and practices add to the dilemma. However vibrant older workers may in fact be, ageism persists in the job market. The current system of private health insurance is further disincentive for employers to hire older employees. Most career paths presuppose entry right out of college and then working one’s way up the ladder over many years, making midlife career changes more difficult than generally acknowledged. And even with all the supposed commitment to lifelong learning, the postsecondary education system doesn’t accommodate older students as well as it might. For example, although I had nearly a decade-and-a-half’s worth of clips from some of the nation’s leading publications as a moonlighting art and culture critic, I received no credit for any of it going through the New School master of liberal studies program, which is pitched to aspiring journalists and other nonfiction writers. Educational assistance, meager as it is, is heavily tilted toward undergrads and not always advantageous to mid-career professionals wanting or needing to make a change.

In addition to individual role models, Freedman highlights several innovative programs that give an idea as to how we might usher in what he terms the “encore society.” The most effective is Troops to Teachers, which helps retiring military personnel, most of whom are middle-aged, transition into the educational field by subsidizing college degrees and then student teaching. The Catholic Church, not typically a hotbed of vanguard thinking, has recently begun to offer widowers a way into the priesthood through the Center for Adult Religious Vocation (though it seems like a gruesome way to make a career move). And for those with a more adventurous mindset there’s the burgeoning area of social entrepreneurship, once a province of the young, offering the potential for people to use various kinds of expertise on behalf of the greater good.

But for any of this to happen, policy changes are needed. One suggestion is to increase the retirement age to 70, postponing Social Security distributions for thousands of workers and allowing time for additional trust fund surpluses to accumulate. (This alone, according to Freedman, would eliminate the so-called Social Security crisis for the foreseeable future.) Extra incentive can be given to employers by waiving their portion of the Social Security deduction for workers over 65. Another idea is to allow workers access to their retirement funds at an earlier age to jump-start new careers. In lieu of this, tax-advantaged education accounts, similar to Roth IRAs, could be set up for midlifers. More visionary is a “reverse GI Bill,” providing college assistance for older workers in exchange for service in areas of need, such as education, healthcare, government and the nonprofit sector. Freedman also offers several ideas to fix healthcare short of recommending a true universal plan. These include lowering the age to qualify for Medicare and letting employees 65 and older collect while they’re still working. Another idea is to extend COBRA, though this takes for granted you’re covered in the first place.

Wonks will debate these and other proposals Freedman puts forth, but average readers will no doubt be most interested in the self-help section at the end of the book. Freedman provides a self-reflection matrix — Are you a “recycler,” leveraging your past experience to enter a new field? Or, are you a “changer” looking to start anew? Are you a “maker,” trying to mold an interest into a career, turning an avocation into a vocation? Whatever your persuasion, Freedman offers online resources, networking ideas and other tips to help you follow your bliss in a more well-managed way.

I’m not sure this book would have changed my decision, although it’s good to know that others have embarked on similar journeys whether by choice or necessity. One thing nobody, including Freedman, mentions about following your bliss is how ignorance (which is bliss) factors into it. If it weren’t for ignorance of all the reasons not to do something, you might not even try. So Boomers of the world, go for it!

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)