Poets get there first. Sometimes you wish someone would listen.

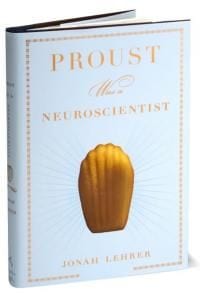

Proust Was a Neuroscientist looks at a handful of the many artists who anticipated, by generations, truths about neuroscience, the mind, the brain and the nature of mental phenomena. The writer is in a prime position to write such a book. Jonah Lehrer worked in the lab of Nobel-winning neuroscientist Eric Kandel and is an accomplished science writer, as well as the proprietor of the blog Frontal Cortex.

Walt Whitman starts it off. For Lehrer, Whitman’s revolutionary starting point is that there’s no soul/body divide. The idea that the soul was somehow of different (usually superior) status or stuff from the flesh had bedeviled human thought for 5,000 years. Whitman sees no divide: The soul “is” the body. Some found that blasphemous (and some still do), but Whitman is already far beyond them: He’s too busy praising the holiness of the body, the mystical sweep of the mind, the God in all and everywhere. It’s what liberates him: Once that wall is down, we are free to see everything as sacred.

Whitman was not the first to have this idea. Sometimes, alas, Lehrer writes as if he was, but it isn’t so. You can hear foretones of it in Anaximander, Anaxagoras, and many other ancient thinkers. Indeed, the Hebrew Bible speaks of “nephesh” — not a “soul,” but a self in and of the flesh, something animals have as well as human beings. Whitman’s was, however, one voice that hauled this idea directly into the modern worldview.

The chapter on George Eliot is especially good. She was an unusually deep, current thinker for a novelist, and you can follow her questing mind as she adopts first Darwinism; then naive, utilitarian determinism; and then, at last, the needful step beyond that, better, closer to the truth: an acceptance that nothing completely explains either us or existence. Human beings always, like nature, will remain mysterious to themselves. Our motives always manage to escape our attempts to explain them.

Eliot steps apart from Charles Darwin, Herbert Spencer, T.H. Huxley, and John Stuart Mill, and in this particular, shows — directly “because” she thinks as an artist — that she was the greater thinker as well as imaginative writer. For too many scientists, engineering explains everything, in a closed-circuit determinist system. In fact, it “has” to. No it doesn’t, Eliot said, and her fiction is great because she did.

Other painters, musicians, even gastronomers come up for treatment here. Most astonishing of all (in terms of neuroscience) is the prescient Marcel Proust, whose fiction nailed memory and how it works. Memory is not so much a faithful secretary recapitulating the past, as it is a creative, fallible, unreliable masquer, presenting images that may or may not reflect what really was. This has powerful significance for identity, since identity, to a large extent, “is” memory. Without the latter, the former disintegrates.

Yet that’s the best we have. Our inner unreliable narrator tells us what we are. Proust’s “In Search of Lost Time” is a monumental demonstration of the workings of memory in personal and communal life. Neuroscience now tells us he was absolutely right. To read Proust is to learn how memory colors, how it constructs, all we know and hope for.

The subtext of this book is that certain entrenched attitudes among scientists ought to go away. Too many science writers assume the infallibility of the science community. But Lehrer shows that this community has been wrong quite a bit, quite wastefully. His account of how Elizabeth Gould’s research, showing that the brain can generate new neurons, to keep its operations fresh and current, is especially excellent. It’s shameful: a brilliant woman’s science long ignored, largely because of a male scientist’s prestige and the lockstep march of obedient labs. There are many good science stories here, but this one is the most instructive.

Lehrer ends by calling for the arts and sciences to take each other more seriously. Several of the good scientists I know do, in fact, have their eye on the arts and heartily wish to build a bridge of fact to the richness of intuition they see there. As to the arts, I must differ with Lehrer: The arts of the last 50 years have embraced the sciences, especially painting, sculpture, gastronomy, music and performance art, but also widely literature. The folks who haven’t kept pace are literary critics — but then, they never do and never can.

Jonah Lehrer has written an enjoyable and stimulating book; he could fill a library with sequels. He is given to the overstatement of enthusiasm, but then, with a fertile subject like this, you’d be enthusiastic, too. And I don’t understand why he limits himself to such recent artists — surely Herakleitos anticipated much in Heisenberg, and so on.

Poets get there first. Proust Was a Neuroscientist is a sparkling introduction to the fact. Makes you wonder why folks have to be persuaded to pay attention to the poets of the moment.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)