A first date. Two 30-somethings meet in a bar. They drink, they eat, they chat, they go through the motions but not, alas, through any emotions. There is no spark between these two. But in the end, what can you do? Not go with him to his apartment? That would be awkward. Much better to engage in emotionless sex, than to face an unpleasant social situation.

Fortunately, disaster strikes. She gets a phone call from a friend, who has been in an accident. She has to leave. The clothes stay on. A feeble promise to get back together. Once the door is shut, his phone rings. A friend – currently playing a video game – is claiming to have been in an accident. But there is no need for this safety lie. Her excuse called first.

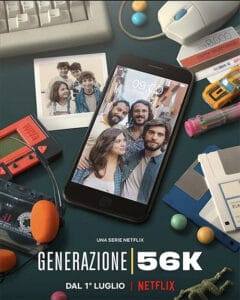

Francesco Capaldo and Davide Orsini’s television series Generation 56k is undoubtedly a romantic comedy. The premise and the plot are firmly in line with the conventions of the genre. The protagonist Daniel (Angelo Spagnoletti) is looking for love. On another date, he meets a childhood friend without recognizing her. And oh boy do the sparks fly this time. But the evening ends without sex, without a kiss, and not even a promise to see each other again. Why? Well, Matilda (Cristina Cappelli) is engaged and soon to be married. When Daniel realizes whom he has met (and fallen in love with) a second plotline emerges.

We are back in the year 1998 and Daniel’s father is one of the first inhabitants of Procida (and island near Naples) to get an internet connection using a 56k dial-up modem. So, what is the first thing Daniel and his friends look for on this miraculous portal to the world? Is it knowledge? Of course not. It is the thing any teenage boy would be looking for. Pornography! Not only do they consume it themselves. They even try to set up a business by copying these images on floppy disks and selling them to the other desperately horny boys of the island. These boys have never held the hand of a real girl, much less kissed one. Sociologist Iris Oswald-Rinner (Sexuelle Revolution?, 2015) coined a poignant term for this contradictory state of experience: “oversexed and underfucked”. But Generation 56k is not so much interested in sociology as in the juxtaposition of different forms of storytelling.

The genres that are crucial for this series – romantic comedy and pornography – are ultimately both narrations of wish fulfillment, although they follow opposite narrative strategies. While pornography is trying to eliminate any form of frustration by immediately offering up its content (the naked body engaging in any sexual act imaginable), the romantic comedy is celebrating frustration by preventing its protagonists from coming together (at least until shortly before the end and almost never in the sense, in which these words would be understood in a pornographic context). While pornography makes sure that its protagonists are always ready and able to perform, the romantic comedy makes sure that its protagonists are always ready and able to say the wrong thing and make the wrong decision – preventing any sort of happiness until the end. In other words, romantic comedy locates the true nature of love and romance in the ability to overcome all obstacles in time, while pornography insists on the benefits of instant gratification – much like the internet, where everything is always accessible. Or at least supposed to be.

Time itself in Generation 56k is indeed in many ways of the essence. Apart from the obvious fact, that the story takes place in two different decades, the question of the past and the present (and of course, the future) is intricately interwoven in the narrative. There are many hints that might be easily overlooked. On his first and second occasions, Daniel tries to amuse his date by retelling and marveling at the intricate time travel plots of the various Terminator movies. Arnold Schwarzenegger’s violent adventures as a humanoid cyborg are not the obvious choice for a romantic evening. But time and romance are apparently linked so firmly in Daniel’s mind that these movies as a topic seem like a promising start for a date.

Matilda, on the other hand, works as a restorer of antique furniture. This places her firmly in the realm of the analogue real and the analogue past, in opposition to Daniel, who works as a developer for apps, his digital “reality”, and the future. Matilda’s can also be read as an act of defiance towards her father – an actor who abandoned the family for his career and whom she hates with white-hot intensity. In a touching episode, we follow the young Matilda as she visits her father in Rome. She wants to know – or better to see for herself – what is more important to him than his family. It turns out her father is recording a commercial, dressed as an ancient Roman soldier, selling toilet paper. The glorious past is ridiculed for the fleeting gratification of fame. It is adult Matilda’s job to restore the dignity of the past.

At the heart of the series lies an emotional time machine. When the proprietor of the local bar dies, he leaves an enormous glass jar to Daniel. For decades, every inhabitant of the island could deposit a letter containing his or her most personal secrets and desires in this jar. The promise was that the jar would only be opened sometime in the future. This gives Daniel an idea for a new app. A text message app that allows the user to decide when a message to a loved one should be sent. Tomorrow, a week from now, or maybe never? The most important things in life – and what is more important than love? – need time. His boss congratulates Daniel on his idea. “You are right. We needed something…romantic.”

If the ability to endure time is one requisite for love in romantic comedy, so is the willingness to forego the easy gratification of the pornographic image. The images that Daniel and his friends download as kids are never really shown. And the only sex that we see is quite chaste, taking place mainly under the cover of bedsheets. Furthermore, this sex is not for pleasure but performed with the halfhearted intent to make a baby, refuting thereby immediate gratification for future happiness.

Even the only direct allusion to the world of pornography in the present storyline makes fun of its strained attempt to evoke pleasure at any cost. Matilda attends a divorce party for one of her friends. Someone has given the recent divorcee a stripper as a gift. But the stripper is rather chubby, and his performance sends Matilda’s friend running away in tears (thereby subverting the male gaze usually associated with pornography).

Generation 56k makes a rather hopeful statement about a generation that is supposedly alienated by the technological devices of its own creation. The fast swipes of Tinder, where we are led to decide in seconds if a person appeals to us or not, cannot be the future (or the present) of how we fall in love. For a genre that is not known for its cinematic prowess, this romantic comedy advocates for something more subtle in the process of seeking a mate, but not less important: the power of a second look. That second, possibly critical look requires something of us that there never seems to be enough: time. The same thing can be said about love itself.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)