Excerpted with permission from Instant: The Story of Polaroid by Christopher Bonanos. Copyright © 2012 by Christopher Bonanos. Published in September 2012 by Princeton Architectural Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or printed without permission in writing from the publisher.

Chapter 1: Light and Vision

If you’re reading this, you probably know what a Polaroid picture is. Even if you weren’t, I probably wouldn’t have to tell you. More than sixty years after instant photography made its debut, “Polaroid” remains one of the most recognizable coinages on Earth. As late as 2003, the hip-hop star Andre 3000 could sing “Shake it like a Polaroid picture,” in Outkast’s megahit “Hey Ya,” and even young people did not have to ask what he meant. Throughout its reign over instant photography—a field the company invented out of thin air and built into a $2-billion-a-year business—Polaroid had no successful competitor, no real challenge to its primacy, until almost its very end.

In the 1970s, photographers were shooting a billion Polaroid photographs each year. Now the whole business has almost vanished. Right around the year 2000, picture-taking experienced a tidal change, as digital cameras swept in and all but cornered the market. Suddenly, photographic film became a specialty item, bought chiefly by artists. Any company that depended on selling or processing film had to endure some rough years of realignment. Eastman Kodak went from its late-1980s peak of 145,000 employees to fewer than 20,000, and filed for Chapter 11 protection in 2012. Polaroid, already struggling with longstanding debt and other problems, got clobbered. Between 2001 and 2009 the company declared bankruptcy twice and was sold three times; one of those buyers went to federal prison for fraud. Polaroid film was discontinued forever in 2008.

Except that it’s not exactly gone. A few types of instant film are still manufactured by Fujifilm, for some older Polaroid cameras and current Fuji models. The last batches of Polaroid’s own film have become highly sought after, with buyers paying $40 or $50, or even more, for a pack of ten expired and increasingly unreliable exposures. A few enthusiasts have taken their analog-revival efforts to great lengths, trying to reinvent instant film anew. The newest owners of the Polaroid trademark have elaborate plans to meld instant photography with the digital age.

After all, digital pictures are instant pictures. The chief advance of Polaroid photography was that you immediately saw what you had done. If the photo was overexposed, blurry, or badly framed, you could try shooting it again, then and there. With a digital camera, you get your feedback even faster, essentially for free.

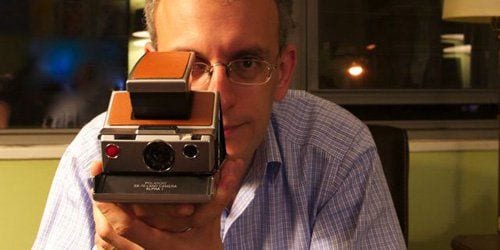

Somehow, though, digital pictures do not draw people together the way Polaroid photos did. Haul one of those old cameras out at a party, and the questions start: “Hey—can you still get film for that thing?” “Are the cameras worth money?” And, once the photos start appearing, “You know, that looks pretty good! I don’t remember Polaroids looking like that. But, you know, we had one when I was little, and… ” This gee-whiz invention of the 1940s, ubiquitous in the 1970s, ostensibly obsolete today, still exerts a weird and bewitching pull.

It wasn’t just for snapshots, either. During Polaroid photography’s heyday, artists like Ansel Adams and Walker Evans sang its praises. Andy Warhol, David Hockney, and Robert Mapplethorpe all shot thousands of Polaroid pictures. Most of William Wegman’s famous photos of his dogs were taken on Polaroid film. He and many other artists, including Chuck Close and Mary Ellen Mark, were (and are) particularly fond of an immense and very special Polaroid camera that produces prints 20 inches wide and 24 inches high. Fewer than a dozen of these cameras were hand-built by Polaroid; five remain active; and one, in New York, is in use almost every day. No digital equipment comes even remotely close to doing what it does.

Children, in particular, react very strongly to instant pictures, whether they’re behind the camera or in front of it. Watching your own face slowly appear out of the green-gray mist of developing chemicals is a peculiar and captivating experience. The older Polaroid materials, those that develop in a little paper sandwich that is peeled apart after a few moments’ development, encourage a different and warm human exchange. Photographer and subject can make small talk as the picture steeps. When the print is revealed, it can be handed over as a gift or circulated around the room. There is no more social form of picture-taking.

When it introduced instant photography in the late 1940s, Polaroid the corporation followed a path that has since become familiar in Silicon Valley: Tech-genius founder has a fantastic idea and finds like-minded colleagues to develop it; they pull a ridiculous number of all-nighters to do so, with as much passion for the problem-solving as for the product; venture capital and smart marketing follows; everyone gets rich, but not for the sake of getting rich. For a while, the possibilities seem limitless. Then, sometimes, the MBAs come in and mess things up, or the creators find themselves in over their heads as businesspeople, and the story ends with an unpleasant thud.

The most obvious parallel is to Apple Computer, except that Apple’s story, so far, has a much happier ending. Both companies specialized in relentless, obsessive refinement of their technologies. Both were established close to great research universities to attract talent (Polaroid was in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where it drew from Harvard and MIT; Apple has Stanford and Berkeley nearby). Both fetishized superior, elegant, covetable product design. And both companies exploded in size and wealth under an in-house visionary-godhead-inventor-genius. At Apple, that man was Steve Jobs. At Polaroid, the genius domus was Edwin Herbert Land.

Just as Apple stories almost all lead back to Jobs, Polaroid lore always seems to focus on Land. In his time, he was as public a figure as Jobs was. At Kodak, executives habitually referred to Polaroid as “he,” as in “What’s he doing next?” Land and his company were, for more than four decades, indivisible. When he introduced its SX-70 system in 1972—that’s the photo with the wide white border that most of us think of as the classic Polaroid picture—Land appeared on the covers of both Time and Life magazines.

At Polaroid’s annual shareholders’ meetings, Land often got up onstage, deploying every bit of his considerable magnetism, and put the company’s next big thing through its paces, sometimes backed by a slideshow to fill in the details, other times with live music between segments. A generation later, Jobs did the same thing, in a black turtleneck and jeans. Both men were college dropouts; both became as rich as anyone could ever wish to be; and both insisted that their inventions would change the fundamental nature of human interaction.

Jobs, more than once, expressed his deep admiration for Edwin Land. In an interview in Playboy, he called him “a national treasure.” After Land, late in his career, was semi-coaxed into retirement by Polaroid’s board, Jobs called the decision “one of the dumbest things I’ve ever heard of.” In fact, the two men met three times when Apple was on the rise, and according to Jobs’s then-boss John Sculley, the two inventors described to each other a singular experience: Each had imagined a perfect new product, whole, already manufactured and sitting before him, and then spent years prodding executives, engineers, and factories to create it with as few compromises as possible.

During some stretches, Polaroid operated almost like a scientific think tank that happened to regularly pop out a profitable consumer product. Land was frequently criticized by Wall Street analysts, and the Wall Street Journal in particular, for spending a little too much on his R&D operation and too little on practical matters. That was Land’s philosophy: Do some interesting science that is all your own, and if it is, in his words, “manifestly important and nearly impossible,” it will be fulfilling, and maybe even a way to get rich. In his lifetime, Land received 535 United States patents. No wonder everyone called this college dropout “Dr. Land”—particularly after Harvard University gave him an honorary doctorate. He advised several presidents (from Eisenhower through Nixon) on technology, and effectively created the u-2 spy plane. Richard Nixon admired his scientific prowess, once asking an aide, “How do we get more Dr. Lands?”

After he quit his advisory post during the Watergate scandal, Land ended up on Nixon’s “enemies list,” and told a friend that he was honored to have made the cut.

He was extremely circumspect about his family life, but we know a little about his upbringing. He was born on May 7, 1909, the son of a scrap-metal dealer named Harry Land and his wife, who was called Matha, Matie, or Martha, depending on which source you read. As a child, Land had trouble pronouncing “Edwin,” and it came out “Din,” a nickname that stuck with him all his life.

Nearly every account of Land’s youth conforms to the classic boy-inventor clichés. Did he once blow all the fuses in his parents’ house? Of course, when he was 6 years old. Did he once disassemble a significant household object, resulting in either parental anger or parental pride? Certainly—either the family’s brand-new gramophone or the mantel clock. Whatever it was, his father was not amused.

He was, it seems, introverted in person but superbly confident when it came to ideas. Accustomed as we are today to Silicon Valley style, this may imply that he was a big nerd, but that’s not right. Land was neatly groomed and notably handsome, with a pleasing, New England–inflected baritone voice, and alongside his scientific passions lay knowledge of art, music, and literature. He was a cultured person, growing even more so as he got older, and his interests filtered into the ethos of Polaroid. His company took powerful pride in its relationship to fine artists, its sponsorship of public television, even its superior graphic design. He liked people who had breadth as well as depth—chemists who were also musicians, say, or photographers who understood physics. He took very good pictures, too.

As a young adult, Land grew close to Clarence Kennedy, an art-history professor at Smith College who was also a fine photographer. Their relationship not only helped refine Land’s eye but also began to feed Polaroid with brainy, aesthetically inclined Smith graduates, handpicked and recommended by Kennedy. It was a clever end run around the competition for talent, because few corporations were hiring female scientists, and even fewer were looking for them in Smith’s art-history department.

Sometimes he sent the young women off for a couple of semesters’ worth of science classes, manufacturing skilled chemists who could keep up when the conversation turned from Maxwell’s equations to Renoir’s brush strokes. In-house, people called them the Princesses.

Land was also extraordinarily tenacious. One of his top research executives, Sheldon Buckler, recalls a story Land told him during a long night in the lab. As a child, Land had been forced to visit an aunt he disliked. As he sat in the backseat of his parents’ car, he set his jaw and told himself, “I will never let anyone tell me what to do, ever again.” You could write that off as youthful mulishness, except that it turned out to be true. Land’s control over his company was nearly absolute, and he exercised it to a degree that was compelling and sometimes exhausting.

He didn’t grow up in a particularly intellectual household. Land once remarked disdainfully that there were virtually no books in his childhood home. Somehow, though, he found himself a copy of the 1911 edition of Physical Optics, a textbook by the physicist Robert W. Wood, and obsessed over its contents the way other kids might have memorized baseball statistics—lingering on one particular chapter, about the polarization of light.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)