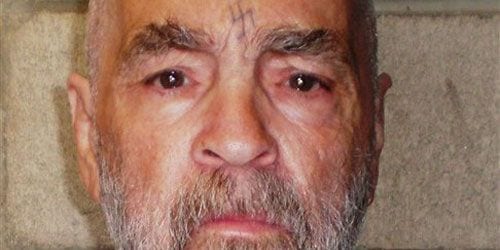

When asked who he is, Charles Manson is fairly consistent. He either makes a series of ridiculous faces and then whispers “Nobody”, or he tells the questioner “I am you”. He is right on both counts.

He emerged from a penitentiary in his early 30s at the height of the hippie movement and his obscure brand of cheap mysticism captured the imaginations of people like Linda Kasabian who, as she claims, was searching for love and God. While the people around him revered Manson, he used their sense of awe to direct their actions without ever becoming fully embroiled in those actions. He wasn’t present during the Tate murders. He tied up the LaBlanca couple but then drove off before the killing. He disavows any responsibility for the murders.

But in a sense his conviction that he is nobody is more telling. His bizarre rhetoric, welding together death and freedom, permits everything while advocating nothing. In a manner of speaking, nobody is responsible for the Tate-LaBianca killings; and that nobody is Manson.

On the other hand, Manson claims that he is within us, that all of us carry a bit of Charlie around inside. Certainly he cannot be too far from the truth on this one. Otherwise, why does he continue to be such a source of fascination (at least within the United States) 40 years after the crimes?

Manson represents the return of the repressed, in Freudian terms. He embodies all of those things we fear may be within us, those things we want locked down. And yet like Satan, Manson remains a figure of allure; his wack-job inscrutability seduces one’s imagination despite the warnings of one’s reason mind. Indeed, there is a reason that Charles Manson remains such a vital (if disavowed) part of contemporary culture. The question can no longer be: “Why would anybody pay attention to this guy?” It now must be: “Why can’t we seem to stop paying attention to this guy?”

The History Channel presents yet another take on the Manson murders, or I suppose I say it presents another version of the same take—that is, the events as seen largely through the eyes of Linda Kasabian, the Manson follower who stood guard outside the Tate home. Kasabian never actually murdered any of the victims, although she was certainly involved in the crimes—as a driver, as a lookout, as a witness.

She became the prosecution’s star witness against Manson and his followers and since then has lived in what we might term “semi-hiding”. She pops up every so often to discuss the murders. The last time was in the ’80s for a special on Current Affair. She is back again for History Channel’s Manson, a documentary that features enacted recreations of the events and interviews with Kasabian, fellow Family member Catherine Share (a.k.a. “Gypsy”), the chief prosecutor of the case Vincent Bugliosi, and Sharon Tate’s sister Debra Tate.

Although anyone familiar with either Bugliosi’s book (Helter Skelter: The True Story of the Manson Murders) or with Kasabian’s court testimony will not learn anything new here, the documentary does a fine job presenting the basic narrative and the reenactments are engaging enough to be suitably creepy. If anything Adam Wilson is too convincing as Charles Manson. In my opinion (humble or not), he far outshines Jeremy Davies in the 2004 TV movie Helter Skelter. (Has Davies been good in anything since 1994’s Spanking the Monkey?)

There are a few anomalies and even downright errors (for instance, who is driving the car when and the timeline surrounding Manson’s meeting with Dennis Wilson of the Beach Boys), but these will only bother the obsessed and the conspiracy theorists (in fact, I would never have noticed them had it not been for my conspiracy theorist brother). For anyone interested in a two-hour, fairly complete overview of the facts of the case, one cannot do better than this.

But what is more interesting to me is Kasabian’s presence. The documentary tries to make some hay out of the fact that Kasabian emerged from (semi-) obscurity in order to discuss her recollections but the truth of the matter is that she merely rehearses the same things (sometimes verbatim) that she discussed in her testimony and her previous interview. Now this, to me, is most curious.

Maybe it is the conspiracy theorist bit running in my bloodstream but two questions (one starkly pragmatic and the other hopelessly speculative) arise. First the pragmatic: why bother bringing her along at all and preposterously claiming to obscure her identity? She added nothing to the record and as for her identity, I could pick her out of a line-up with no problem. Sunglasses do not a disguise make.

The more speculative question, of course, involves the utter consistency of her testimony. Memories change over time. Even if we maintain the basic facts, different details become emphasized, things that were earlier omitted come to the surface and other things fall away.

More to the point, after 40 years, one would think that her devout fascination with Manson’s manner of being would have dissipated, better yet would have rotted with disgust and a deep, personal sense of betrayal. After all, according to her, Manson sold her a bill of goods that led to depraved murder. But when she talks about meeting him and listening to him speak, she still describes the experiences as beautiful as though they had granted her access to a divine vision from which she has yet to awaken.

Purists may complain that Kasabian’s “re-emergence” does nothing to further our knowledge of the Manson case. They would be right. But watch her face (don’t worry it is hardly obscured). Listen to the sound of her voice when speaking of Manson before the murders. Hear the adoration. Ask yourself why she is still so drawn to him. And then ask yourself why you are still so drawn to the notion of Charles Manson.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)