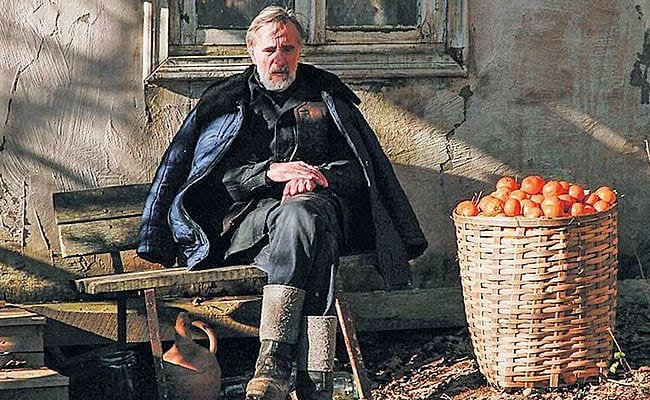

Zaza Urushadze’s Tangerines (Mandariinid) is a quiet study of ravages. The opening credits appear over aging hands fashioning wood slats with a table saw, the sawdust pluming into the air before settling on the woodworker’s clothing. The hands belong to Ivo (Lembit Ulfsak), a white-haired Estonian grandfather working alone in his shop in Georgia.

It is 1992, and war has broken out between the Georgians and Russian-supported Abkhazians, resulting in a mass exodus of most ethnic Estonians back to their homeland. Ivo and his neighbor Margus (Elmo Nüganen) have stayed behind in their now mostly deserted village. Margus is determined to harvest and sell his crop of tangerines and Ivo is making wooden crates for them. It’s too big a job for the two older men, but Margus has secured a promise from an Abkhazian major that he will send 20 soldiers for one day to help bring in the harvest. Though Ivo has doubts, wondering why “soldiers would pick tangerines during wartime,” they hope for the best.

That hope can’t shield them from the fighting, however. After Ivo shares a brief conversation with a couple of Chechen mercenaries passing through the area (they’re fighting for Abkhazia), he soon comes upon them again, one dead and the other wounded. A van nearby holds several dead Georgians, and one who is barely alive. Ivo and Margus decide to move the injured men to Ivo’s home to care for them.

This is the setup for the main tension of the film. Two enemies, the Chechen Ahmed (Giorgi Nakashidze) and the Georgian Nika (Misha Meskhi) are confined to the same space and must learn, with Ivo’s mentorship, to see one another not as enemies but as fellow human beings. Their starting point is Ivo, whom they both respect for saving their lives. When he insists, they agree without much resistance to a temporary and uneasy truce, or at least not to kill each other in their host’s home.

This situation offers plenty of chances for discussion of difficult questions, long-standing enmities, and ethnic conflicts. Repeatedly, the men identify themselves, naming their allegiances, explaining their motives. When Margus and Ivo discover the dead Georgians and Chechens, the only visual differentiation they are able to make is that the Georgians are “mere boys” while the Chechens are older. When some Abkhazians stop by Ivo’s, a disgusted Nika pretends to be Chechen. These moments illustrate just how entangled and divided their histories are. Again and again, the men must explain whether they’re Russian or Georgian, Chechen or Estonian. None of these identities is outwardly marked, by appearance or language. The men tell one another and themselves who or “what” they are. Sometimes their interlocutors believe them, and sometimes they don’t.

For Nika, history justifies the Georgians’ cause. As he sees it, the war is an invasion of Georgian land: joining the fight was his only option, a decision he took, he recalls, without even saying goodbye to his mother. He sees this history, the one he knows, as a function of education and civilization. He assumes that Ahmed knows nothing of history, that he’s uneducated, unable to understand what he is fighting for or against.

But, of course, Ahmed does have history and his is very different from Nika’s. For Ahmed, they are not on Georgian land, but Abkhazian. More specifically, he jokes, he and Nika are sitting on Estonian chairs on Abkhazian land. While Nika is hardly amused, this moment illustrates several points. First, it underscores Ahmed’s position as a mercenary. He can make light of whose land they are sitting on because he is there for the money, as he readily admits. It’s a fight he can take or leave, when he gets tired of it.

But Ahmed’s acknowledgement of Ivo’s Estonian chair tells us something else, too. Both he and Margus were born in Estonia, but while Margus plans to return with his tangerine money, Ivo will not, despite his obvious affection for his family, and particularly his granddaughter, who already went back. There is another history then, of the Estonians transplanted in the Caucasus for over a century, then forced back to a native country most had never seen. What of their history with the land where they’ve grown up, their rights to it?

Ivo never argues for a side for or against the others. All three of them are alien, none is at home. For all the complications, Ivo’s decision to stay inspires the other men’s respect; they believe him to be brave. He is undaunted by the mercenaries he has saved and shrewd in his handling of other soldiers that pass through the village. Even his determination to bring in the tangerine crop, though not fully understood by Nika and Ahmed, seems courageous, a dedication to survival despite the violence erupting around him. Bringing in the tangerines is may be a matter of money, but it is also, as Ivo offers, a metaphor. It would be a pity, he says, if “a beautiful crop would perish.”

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)