Since the beginning of modern improvisational American theater in the 1970s, actors and directors have hailed improv as a method for accessing their greatest creativity, so much so that some commentators have referred to it as a nigh-religious “belief system” (Seham xx-xxi; McLaughlin 49). In recent years, much has also been made of improv’s potential to change interpersonal communication for the better. But these discussions have not considered how improv may have already contributed to cultural change (Alda 2017; Kulhan 2017; Lane 2011). Johnstonian improv (named for improvisational theatre founder, Keith Johnstone), particularly the mock-competition style known as Theatresports, makes for an effective theatrical performance because of its duality: the audience sees the performance but is also kept aware of the performer’s identity as a performer by the imagined competition (McLaughlin 2013).

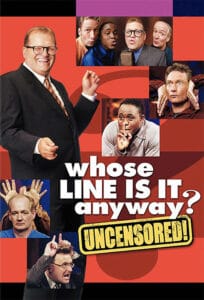

In the case of Whose Line Is It Anyway? a Theatresports-style televised mock game show which constitutes the public’s main association with improv, the feeling of seeing a real performer engaged in a competitive performance serves not to illuminate the idea of performance itself, but to allow the audience to relate closely with the performers as people rather than characters. Cast members recur, with Drew Carey in the American series in place as the permanent host, and the main performers appear in almost every episode.

The audience is able to build a rapport with the cast and respond to jokes that continue running across multiple seasons. This rapport, and the show’s status as low comedy, meant that millions of people invited it into their homes on a weekly basis – more than eight million households in the US alone (the show had versions in multiple countries) every week during its peak in the late 1990s and early 2000s (Nielsen). Fans continued to watch reruns long after new episodes stopped airing, and persisted in talking about the show enough to warrant a revival program that has continued running from 2013 through the publication of this article.

As ComedySportz UK founder and manager Braínne Edge reported in an overview of improv on television, “People don’t like Whose Line Is It Anyway? because it’s improv, they like it because it’s funny.” (2010) Its particular style of humor was relatable and everyday, built on audience suggestions and common cultural tropes. However, because of the quick pace of improv, it also often relied on surprise and subversion of expectations to provoke laughter and had just enough of an edge to push mainstream boundaries.

The show developed a particular reputation for comedy based on imagined homosexual desire between cast members, as well as the vocal and dance performances of the sole black cast member. While these jokes often included self-deprecation, and occasionally a style of comedy called “mocking the weak” or “punching down”, the overall effect of repeated exposure was to normalize these topics and create repeated empathy for marginalized people.

Examples from Whose Line Is It Anyway? episodes are cited by season and episode number.

Who Is That Black Man Anyway?

Whose Line’s most visible and talked-about representation of diversity came in the form of black actor, singer, and comedian Wayne Brady, who appeared in 212 of the original 220 episodes. Improv comedy boasts few black performers, and the term “diversity” is usually used as a euphemism in this context – “lack of diversity” signifies “absence of Blackness,” and continues to frame the discourse from a white perspective (Buch 2014). Researcher Michel Buch points out that “the absent are being blamed for their absence” without any real interrogation of the reasons why they might not be present. It is in this context that Brady’s visibility becomes inherently noticeable, and thus controversial.

Brady’s position as the only black performer on a show popular with white audiences led to black commentators’ accusations that he was “not black enough“, and that his musical performances on Whose Line Is It Anyway? and later shows amounted to “cooning”, or entertaining white audiences with stereotypical African-American behavior in exchange for a small measure of acceptance or social status. Some comedic elements do seem to be included at Brady’s expense, particularly the musical segments “African Chant” and “Mo-Town Group”, in which he improvises songs in these genres and the other performers act as a satirical backup group.

His musical and vocal skills made him the “secret weapon” of the new show, (Hall and Baker 2016), but these segments are generally treated as embarrassing for everyone involved and provoke jokes like “they’re not letting me back in Africa after that one” (2.06) from Brady, or “take it away, Wayne and the Crackers” (4.32) from Carey. Other games give Brady characters to enact such as “a Jamaican sex god” (3.04) and various black celebrities like James Brown, Tina Turner, and Michael Jackson.

The clearest acknowledgment of how fraught this situation may be comes in the outtakes, rather than an aired episode. Preparing to shoot a scene after Brady has “won” the imaginary competition and will be sitting at the desk, he jokes, “Why the brother gotta be at the desk?” to which Carey responds, “Listen, you did your singin’ and dancin’, just sit down,” and Brady answers “Okay, Mistah Carey!”. The fact that the exchange occurs in outtakes demonstrates that the show’s editors knew it was problematic, but also that they did not want Carey and Brady drawing attention to that reality.

Brady has said in retrospect, specifically responding to accusations of cooning, that he purposefully avoids using black jive or minstrel moves in his performances, but rather accesses a history of black performances that were not purely for white consumption. Examples include his admiring impressions of black celebrities, as well as his own discretionary choices. When prompted with “a sixties girl group”, for instance, he chooses to perform as multiple members of a clearly African-American ensemble (1.11).

Some of the criticism he experienced may have come from his reluctance to play up blaxploitation-style “thug” characters, which he saw as problematic. However, his willingness to play generic black characters for a white audience at all may be equally to blame for his reputation. In retrospect, it is difficult or impossible to tell if the jokes he made were, from the audience’s perspective, at his own expense.

Another possible source of criticism is that in his career, Brady has not made a point of working with other black entertainers or using his position to bring others forward with him, but the rest of his career and much of that criticism is outside the scope of this essay. For current purposes, it is enough to note that at the time he was performing on classic Whose Line Is It Anyway?, he did not have the influence to make those kinds of structural changes on the show.

However, it can be noted that although there are few opportunities for him to interact with other black people onscreen, he seems to be especially pleased and protective on the one occasion when a black audience member is chosen to come on stage (4.18), and throughout the episodes in which Whoopi Goldberg appears (5.03). In one episode, after playing the African Chant game, Wayne runs out to apologize to the one black couple in the audience, bemoaning that “one brother comes out to see a taping and that’s what he sees” (7.08).

Still, potentially-pejorative references are far outweighed by Brady’s own, in which he consistently draws attention to his blackness. Often, his jokes are responses to unrelated uses of the words black and white. Others are visual puns, such as Brady rolling on the floor in response to another player’s reference to “rolling blackouts” (5.13). Still others depend on the audience’s understanding of his and the other players’ races, and their associated expectations, such as “trust me, you’ll blend in, in Compton” (1.16) or “when I was the darkest child in my village in Sweden” (3.32).

More pointed examples also exist in which Brady explicitly challenges stereotypes, often during the setup for a scene. We see this in his performances where he says, “Why do I gotta be the Haitian man who’s been unfaithful and is the victim of a voodoo attack?” (4.08), “why a brother gotta go first, don’t you watch horror movies?” (7.21), and Brady exclaimed, “hello guide!” after the scene prompt references “a tourist and his guide”, subverting the unstated expectation that a native guide would be a person of color (4.24).

Further, Brady consistently uses comedy to point out modern-day American racism and the legacies of slavery. When short-joke prompts involve states and any player mentions a southern state, Georgia-born Brady usually takes the opportunity to remind the audience that his experience of the South as a black man is more dangerous than their own (6.02, 4.24). Jokes such as a horrified “come and hang out in Alabama” (6.08) (referencing lynching), or using “wanna go down south” as a pick-up line while wearing a hat decorated with a confederate flag symbol (6.06), defuse a fraught situation that Brady creates for himself. (This mechanism is similar to that used in self-deprecating comedy, as discussed in the section on gender.)

Brady creates a similar tension in references to the Ku Klux Klan (2.18, 7.08) and to police profiling and violence (3.11, 7.20). In one early episode, he raises a Black Power fist in response to a prompt about getting arrested (2.21), and after a musical performance as the entire hip-hop group Public Enemy that also included raising the fist and using the phrase, “fight the ticket power”. Carey jokes, “That’s scary to people in Orange County, the Black Power stuff” (3.29).

In one additional episode, Brady is prompted to play a thief, to which he responds with “Why I gotta be the thief?” and another power fist (4.13). Carey’s joking answer is, “You know, maybe you should count your blessings. If this was NBC you probably wouldn’t even be on this show.” All these examples show that despite a growing reputation among some black audiences for being “not black enough”, Brady was deeply aware of his status as black and of the stereotypes that plagued black characters.

Are Brady’s jokes then examples of him asserting his blackness? Was the show pushing him to make mocking “black jokes”? Or was the show using his presence to make pointed jokes that otherwise could not be made? Or do they simply represent a different set of cultural assumptions that inform Brady’s on-the-spot decisions, without intentional purpose? In all likelihood, all these elements were at play. However, as Michel Buch put it in his study of black presence in improv, the first step is “for the Improv community to acknowledge that raceneutral and apolitical Improv, in form or content, does not exist” (12).

Brady was a highly visible black entertainer on Whose Line Is It Anyway?, and he used that platform to repeatedly remind the audience of his blackness and the cultural baggage of racism in America. The tone of the jokes was sometimes unclear, but as will be illustrated in further discussion of Whose Line Is It Anyway?’s gay jokes, this uncertainty meant that “black jokes” were not generally negative, but often confidently matter-of-fact or even celebratory. Either way, they were always present, and although empathy’s effects may be negligible in a specific instance, the feeling can create changed attitudes and behavior over repeated exposure (Keen 2007; Hakemulder 2000).

What Is It About Women Anyway?

There are no female performers in the main comedic lineup, musical performers notwithstanding, and female guests’ comedic standing is fraught from the beginning. Self-deprecation, a hallmark of standup comedy, functions both to “placate” the dominant group and “reassure” other members of the marginal group (Tomsett 2018). Therefore, “any self-deprecatory utterance in live comedy performance will always simultaneously both reinforce and challenge hegemonic views of women and their bodies”, since it is directed to and received by both groups at the same time. Self-deprecating jokes can raise an issue that provokes tension, such as racism or sexism, while simultaneously defusing that tension by abasing the person who has made the joke.

However, although women certainly make self-deprecating jokes on the show, this type of humor is not their signature and is more associated with Whose Line Is It Anyway?’s (white) men. Instead, working within the particular constraints and considerations of improv comedy, female performers seemed to struggle more in the ability to control scenes and characters as they developed.

Ellie Tomsett’s research on standup continually demonstrated that male audiences resist “being amused by women”. Such amusement would represent the ceding of cultural power, allowing women to surprise men and direct scenes in unexpected ways, while also potentially laughing at and criticizing men. This makes it particularly risky for female performers to take control of the performance space or the direction of an improvised scene.

Kathy Greenwood, despite being a frequently recurring cast member, almost invariably plays a reactive role without attempting to affect the flows of her scenes, but her few departures from her this role are particularly illustrative. In two games of Helping Hands, several seasons apart, she is presented with particularly female situations and does not play them for laughs. In one, she is purchasing a pregnancy test and her character seems both overwhelmed and frustrated with the cashier’s questions about it (4.22). In another, during an allegedly romantic rendezvous, Stiles’ character grabs at her and she responds with “I’m ready to leave,” “I would like half a glass of wine,” and “you’re scaring me” (7.10), which is anything but funny, and the audience does not laugh at the line.

The predominant form of gender-related comedy on the show comes from male performers’ jokes in the form of sitcom-style marriage humor, e.g., “Wives live longer than husbands because they’re not married to women,” for instance (1.13), or the divorce-themed hoedown (4.21). Female performers may receive prompts to play nagging wives (3.02) or “clueless teenage girls”, (4.08) and generally play along. However, it seems that Greenwood resisted trivializing certain content, either consciously or unconsciously.

Additionally, the games Living Scenery and occasionally Party Quirks are both examples of games that present very different situations for female players than for men (4.05, 4.07, 4.12, etc). The games and prompts largely function as excuses for male players to handle female performers or audience members, which is presented as inherently funny, and the player has no easy way of declining to be touched other than cause a scene in front of an audience and cameras. Few performers are willing to go to such lengths, risking censure from audiences, co-performers, and employers.

Dead Bodies, a later addition to the game lineup, functions the same way. The inappropriately tactile nature of the games is inherent to the comedy and is consistently pointed out, but nowhere more obviously than in the Living Scenery game played with two special-guest Playboy Playmates, when Carey explains the game and says to them with a shiver, “I know, it’s kinda creepy, huh?” and they all carry on with the game (5.04). In another exchange, actress Denny Siegel announces “I feel dirty and used” after a sketch, and Carey jokes “Hey, great – 1,000 points!” (8.06). (It should be noted that Carey had limited control over the games, and in the context of analyzing Whose Line Is It Anyway?’s broadcasted content, his statements likely reflect an awareness of problematic elements of the show and its production.)

Just as frequent as jokes at women’s expense are instances of male performers playing female characters in a kind of prop-less drag. This humor generally combines poking fun at stereotypical women with teasing the male performers for not being very realistic women, perhaps also with an element of laughing at men for acting like women in the first place. It’s another fraught comedic situation, but a familiar one to American audiences, with little risk and little relevance to women themselves.

In short, the show considers it perfectly acceptable for men to perform women’s roles, but real women’s issues are not as prominent, or not as funny, since they are real, and improv comedy is built around creating comedically simple characters. This does not necessarily indicate overt sexism from the performers or the audience, since they do not laugh at a woman’s potential victimization, but when Mochrie, playing a female character, declares “you men have no idea the suffering women have” (6.01), at least one audience member cheers in appreciation.

- 'Improve Nation' and the Birth of Saturday Night Live

- A Capella Punk: What's Happening to Alternative Comedy in the US?

- Haven't You Learned How to Take a Joke? The Comedy on Campus Debates

- Stand-up, Scandal, and Satire: On Iain Ellis' ‘Humorists vs. Religion

- The Rebel Rockin’ Roots of Punk Rock Humor

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)