‘Stop me, if you think you’ve read this one before.’. Simon Goddard began his first music biography, 2013’s Songs That Saved Your Life, in a witty pastiche of the unique voice of Stephen Patrick Morrissey. One need only take into account the efforts that followed and it becomes apparent that Goddard’s work is not intended to recap old ground, but in fact to unearth a new rhythmic terrain; he shoots into super fandom by illuminating the creative processes of both the bands and the most idiosyncratic of frontmen he covers.

Take Mozipedia for example: an eloquent and exhaustive encyclopaedia of all that can be known about the music of Morrissey and The Smiths, 2009. Or Ziggyology, in which Goddard documents the mythical evolution and glamourised collapse of Bowie’s eminent persona, Ziggy Stardust and the cultural influences that constructed him, published in 2013. These two examples reign supreme in exemplifying the way in which Goddard implements spectacular language, combined with meticulous research to get inside the minds of his musical subjects and, ultimately, create innovative works that have not been read before.

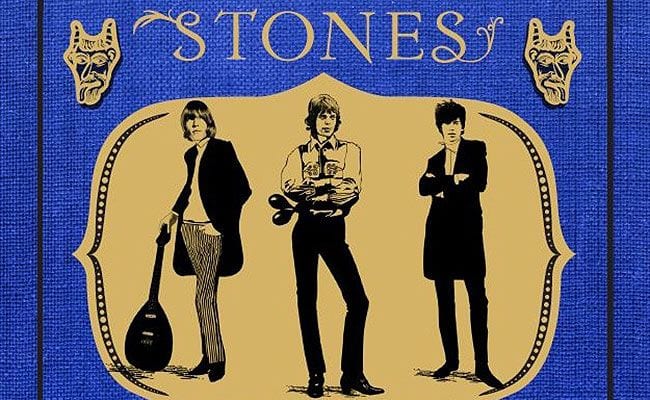

In his fourth music biography, Goddard has taken his pen to wrestles with the momentous debacles of the Rolling Stones, a band whose musical legacy and notoriety has spread fifty 50 years and is still rolling. This does leave one pondering over what more could be written about such a tour de force. The answer? Well, in a style that mimics that of an 18th century novel, of course.

Through his preface, Goddard reinvents himself into the persona of an author devoutly influenced by late 17th century satirist William Hogarth, along with Hogarth’s ‘blessed friends’ Laurence Sterne and Henry Fielding. Corresponding with the literary spirit of the century he is mimicking, one in which ‘sentences unfurled in rolls of silk’ and ‘entire paragraphs were embroidered with jewels of wit’ Goddard invokes Hogarth as his ‘immortal and majestic muse’ in hope that he, like Hogarth who painted many a great novel can ‘write as great a painting as my pen is worthy’.

In this vein, Goddard He decorates his innovative take on the bawdy tale of the Rolling Stones with satire and satisfaction, reinventing his musical subjects as ‘five of the boldest English rogues as have ever trodden their native soil.’. This, wrapped up in a rock ‘n’ k-n-roll picaresque narrative, accounts for the apropos titling: Rollaresque: or, The Rakish Progress of The Rolling Stones.

The book is set into four separate ‘books’ entitled ‘Heirs’, ‘Orgy’, ‘Gaming’, and ‘Madhouse’, tracking the tales of debauchery, the trials (quite literally) and tribulations of the band. It even includes an intricate map of London and a humorous glossary of the ‘old and vulgar tongue’ to aid the modern reader in translating the intricacies of Goddard’s more archaic terminology.

Through each section, Goddard charts the band from ‘the designs of mother puberty’ to their primal flourishing under the flamboyant hand of their manager, Andrew Oldham. This marriage of mischief thus saw the Rolling Stones transformed into the archetypal rock ‘n’ roll bad boys, over which female fans aplenty began to ‘drool at the faintest whisper of’.

Through emphasizing the growth and impact of the band in this way, Goddard brilliantly encapsulates the Rolling Stones as what was needed to bring the air of ‘satisfaction’, that is, the dynamic tenor of R&B, in order to satiate the stiflingly oppressive tone of ’60s England he sets up.

So, why bombard the modern reader with such an ornate narrative style? As stated, Goddard is not one for merely imitating a tale and thus, he marks that his brazen intention in Rollaresque is to prize the infamous bands’ story from the ‘ungrateful paws of this epoch’. He demonstrates that this modern age is ‘so frightened of expressive prose and its power to stir the soul from automated drudgery that some humans, even those of purportedly high intellect, ignore the infinite riches of our glorious vocabulary’.

It’s exactly the flagrancy and lyricism incited here that affords Goddard countless opportunities to poke his quill in jest at each of his rogues. One Mick Jagger is introduced as ‘a boy of noticeable facial orifice, his mouth large enough to swallow a suckling pig, yet his birdlike physique suggesting such advantages were rarely exploited’. Despite his depiction being quite the mouthful, on occasions such as this one, Goddard’s wit allows the modern reader to draw breath to titter, at least.

This satire is further captured as Goddard depicts the explicit rivalry between the Rolling Stones and the ‘Beatles Pop Group’: an antagonism that formed a monumental schism in the ’60s for many a ‘wretched maiden’. In contrast to his ‘shaggy haired monsters’, Goddard portrays The Beatles as sapless automatons: all dressed in suede and ‘identically combed in the concealment of forehead’. Displaying that his own loyalties lie with the Stones, Goddard pulls no punches in belittling the integrity of the Liverpudlian group, at one point describing Ringo Star as ‘a fellow of quite explicit idiocy’, and George Harrison as a man ‘so quiet as to provoke immediate mystery as to whether he was a pensive genius or a mute simpleton’.

Despite shrewd wit, the way in which Goddard manipulates his elaborate literary style to draw upon all the aesthetic foibles of his characters (he comments relentlessly on the size of Mick Jagger’s mouth) means that they end up cemented into an undeveloped gaggle of satirical caricatures. In this way, the modern reader begins to take Goddard’s chronicling with a pinch of salt.

Despite this, the saving grace of Rollaresque is that beneath the obvious humor, there’s a clever and insightful spirit of writing. This comes with the unusual development of Brian Jones’ character as the melancholic heart of the Rolling Stones’ sorry saga. Goddard thus creates a story of the Rolling Stones that diverges away from the usual focus on the love/hate matrimony between Mick and Keith. The wretched lyricism of the language Goddard adopts allows him to paint a glorious picture of Jones’ dissent into alienation (both from himself and the band), buttressed by Jones’ growing reliance on cannabis (The ‘Indian Hemp’), the possession of which leading to his arrest in 1967.

Through Jones, the reader gets a real sense of his true-to-life bittersweet texture and all his tragic blemishes. Furthermore, rather than describe the ‘gruesome particulars’ of his eventual death, Goddard perpetuates the tragedy and leaves Jones as a mere silhouette of a character in comparison to vigorous vagabond with whom the Stones’ story begins. Goddard writes: ‘[Brian] would appear only occasionally, a pale apparition in the control booth, his head lolling to the heavens as he listened to the Stones make less of the desperate nothing they started with […] He was but a spectre, a twitch in time’. This marks the darker tenors of a truly pained character who, while not without his faults, beacons a consciousness of the fatality that lies within fame.

Sadly, Goddard’s 300 age account of the Rolling Stones, as it ‘hurtles without pause’ from 1962 to 1967, doesn’t leave the reader a lot of room to breathe in much of the satisfaction that bookends Rollaresque. The shortness of his chapters don’t completely deter from the fact that the narrative is dense and trudging in points, with the author reveling a little over-indulgently in his ‘expressive’ prose. Despite the melodic rhythm Goddard creates with his very specific literary style, he skimps on the finer details pertaining to the actual music created by the band. From a writer who has been heralded as a trailblazer in ‘rescuing the music from the myth’, this falls short of the mark.

Still, there are undeniable elements of literary grace that shine through. Goddard’s constant allusions to ‘satisfaction’ (mimicking the band’s 1966 single of the same name) placed alongside the metaphors of ‘milk’ and ‘oxygen’ are crafty literary devices; they exemplify a level of dependency and necessity which highlights that the musical influence of the Rolling Stones flows with the vitality of a life-line and shows no sign of abating.

Rollaresque then, not unlike its anachronistic narrative, is an awkward book to place in the rating stakes. It may not branch a comprehensive musical history of the band, which may be less than satisfying for the avid Stones worshipper but, undeniably, there are many books out there that do.

The novel ends with Mick and Keith released from their custodial sentences, raising their respective drinks and ‘curling their lips into a pair of devilish grins’ exclaiming ‘Satisfaction!’ Indeed, for the modern reader, the taste of satisfaction afforded from Goddard’s tale is one quite bittersweet.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)