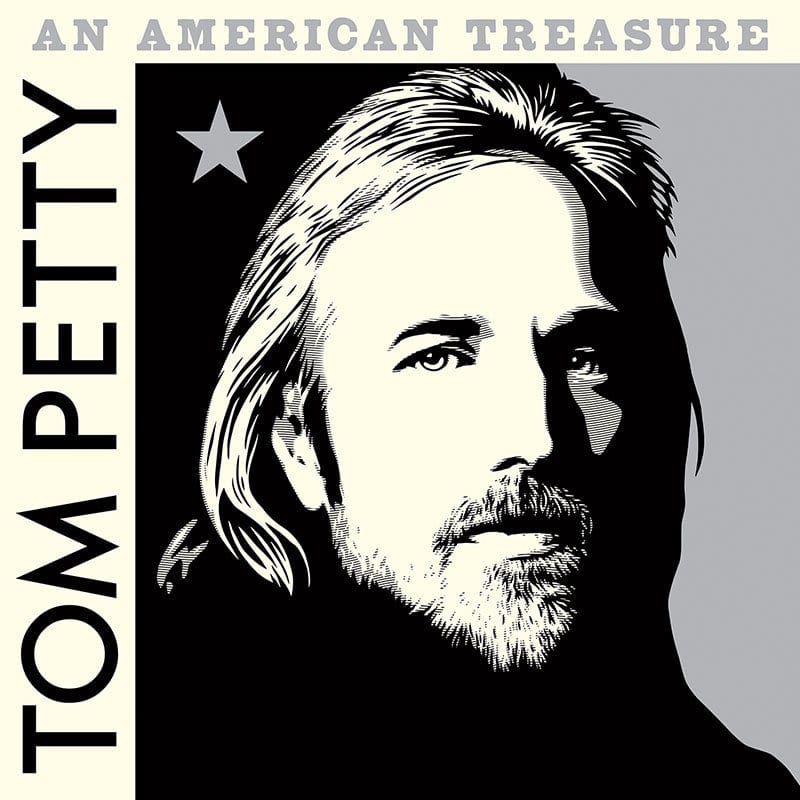

Tom Petty was a workhorse. When he passed away just days after the end of his 40th-anniversary tour with the Heartbreakers, the fans grieved not only in the nostalgia of their past experiences with his music but also very definitely for all the potential future albums that would no longer be forthcoming. But the archives! That was the mantra echoing inside our collective holding of breath. The band family and the blood family knew it, too. So they delivered Tom Petty: An American Treasure.

Petty was already in progress on an anniversary edition of the Wildflowers album, and the record company could’ve gone in for its quickest available buck, but they didn’t. Sure, it’ll probably come out some day soonish, but an expanded re-release package of a single album for Petty’s first posthumous release simply wasn’t going to rise sufficiently to the level of a capstone for a musician who truly was an American treasure. Instead, we have a four-CD box set.

The first of three tracks released in advance was “Keep a Little Soul“. It was an ideal opening volley for several reasons. As a stand-alone composition, like so many of Petty’s songs, it feels entirely current even though it is more than 30 years old. He had a knack for melodies that can stand the test of a very long time, tunes that echo back to classic rock riffs yet remain at home on contemporary rock radio playlists. “Keep a Little Soul” is a typical example of one of his biggest strengths, yet it also reminds us of where he was weak. Long After Dark faired quite poorly in comparison to his four previous albums, and this deleted track, therefore, calls attention to an entry in Petty’s oeuvre that remains underappreciated. For those focused on lamenting the loss of future albums, it’s a gentle nudge toward the back catalogue. For those dwelling generally in their grief, the lyrics insist that we buck up and carry on. They argue that keeping a little piece of him in our hearts is all that really matters anymore.

The second teaser was “You and Me (Clubhouse Version)“. The original cut appears on The Last DJ, Petty’s scathing criticism of the corporatization of rock radio and the unethical excesses of a capitalist music industry generally. Naturally, it was hard for the record company to want to promote their own unmasking from such a trusted source, so this second volley also points us back toward a gem that never got proper circulation. The first two advance releases together display a mild vindictive streak that no doubt would’ve made Petty chuckle. The “clubhouse version” also emphasizes that the band could often achieve several equally album-worthy cuts of a song, sometimes in wildly different styles. Their outtakes are usually just as solid as their commercial releases.

The third teaser, “Gainesville“, was cut during the Echo sessions. Petty almost never played songs from that album in concert, so this unreleased material has the weight of a particularly deep track. It harkens back to his hometown with a mid-tempo restraint that neither romanticizes his roots by giving them an anthemic treatment nor sinks into balladry that would constitute a sad-sack approach to his subsequent successes. He instead walks the line, acknowledging that for better and for worse, there was a span of his life when Gainesville was a big town. It’s an appropriate retrospective. Even though these three advances released were culled from three different decades, Petty’s vocals are so shockingly consistent that it would be hard to tell their chronological order just by listening.

The American Treasure box set somewhat utilizes chronology as its organizing principle. During his lifetime, Petty repeatedly remarked that he wished people still appreciated albums as an entire package, rather than a la carte downloading just a hit single here and there, and he took great pains to consider how the tracks on a given album should be sequenced. In general, he went for narrative or emotional arcs. Of the several compilation albums he made, two of them have four or more CDs—Playback had six discs with a whopping 92 tracks and The Live Anthology had four discs with 48 tracks. Both of those adhere less to linear time and more closely to themes; Playback even explicitly states them (other sides, through the cracks, the big jangle, et cetera). An American Treasure clocks in with 60 tracks and each of the four discs loosely adheres to one decade—1970s, 1980s, 1990s, and 21st century. As with The Live Anthology, each disc functions like its own concert with a proper beginning, middle, and end.

Each disc has a variety of songs on offer, from demos to alternate studio takes to unreleased singles to live recordings. As usual, there are some delightfully surreal odds and ends that showcase the band’s sense of humor, from a 1977 radio spot featuring the voice of Mudcrutch’s Randall Marsh to a show intro provided by Kareem Abdul-Jabbar to Petty’s own concert announcement to clear the aisles at the Forum. There is also some acquiescence to fan expectations of his canonical influences, like an “Insider” duet with Stevie Nicks and a nod from Roger McGuinn on a version of “King of the Hill” that was recorded in a hotel room.

There are a couple of stand-out tracks on each of the four discs. On disc one, the version of “Anything That’s Rock ‘n’ Roll” includes a variety of different inflections and pauses than the album version. The vocal appears to be straining to pull the tempo forward slightly faster into a more garage rock angst than the Buddy Holly polish found on the album version. It’s almost as if Petty’s taking a self-conscious stab at a British accent. There’s a fancy lick with a hard stop at the end, instead of the fade out on the album. The version of “Louisiana Rain” featured here shows much higher notes from Mike Campbell, jabbing through the vocal like fat raindrops and consequently pushing Petty toward a more soulful interpretation. He shows a little more effort to articulate the lyrics clearly, too, and the result is a less slurry Southern sound on this version. An unreleased Mudcrutch single, “Lost in Your Eyes”, showcases some of Petty’s finest crooning against a backdrop of R&B-flavored horns.

On the 1980s disc, what stands out is the effort to workshop and experiment with the music, either with chord progressions or the extent of the filler notes. Many of the tracks feature extended instrumentals either as introductions or at the bridges, and occasionally there are different instruments altogether, as in the case of a live cut of “Even the Losers” that manages to both reduce the tempo and add bluegrass elements with Campbell on mandolin. It’s clear throughout this section that the band is pushing back against that rigidity of style commonly heard during this decade. Even Stevie Nicks was feeling it, and when she joins in on a demo of “The Apartment Song”, she works off a more dissonant, layered strategy of in-the-round backup, rather than straight harmonizing as she and Petty usually did. And since I wrote an entire book about it, I’d be remiss not to mention that the version of “Straight Into Darkness” here is fully 40 seconds longer than the one on the album. It features less twinkly guitars at the bridge and ends amusingly with Petty noting that, “we got Iovine boppin'”, which was notoriously hard to accomplish at this juncture near the end of their production work together.

The 1990s disc taps into Wildflowers, showing a vision of the album that puts drumming further forward in the mixes. This is best exemplified by the very heavy hi-hat on “Crawling Back to You”. In this case, we see how Petty could easily have given in to the temptation to produce the same sound everybody else got interested in during the rise of the drum machine, but after hearing how it came out, he and Rick Rubin steered their noise in another direction. The stand-out track that didn’t make the original album is “Lonesome Dave,” a hilarious, raucous, up-tempo honky tonk number that is deeply danceable. Petty leans hard on the most nasal part of his accent, while the instrumental is full of fired up electric guitar. It’s got its claws sunk into a serious boogie more than almost anything else on the Wildflowers album and sounds more like the late 1970s stuff, plus there is some killer organ at the bridge.

The fourth disc plants a flag firmly back in Florida. The Heartbreakers are sometimes accused of being an L.A. band with a quaint Southern backstory, and perhaps much of their music in the 1980s and 1990s did lean more West Coast than Dirty Deep. But with tracks like “Bus to Tampa Bay“, it’s possible to draw a straight line from Southern Accents to its spiritual kin in Hypnotic Eye. Petty’s work in the new century really did harken back to his roots with a proper degree of authenticity and respect, as heard here in the live recordings of stuff from Mojo and the extra material from his Mudcrutch revival.

Nowhere on these four discs is there a version of “American Girl”. And there shouldn’t be. For those cave dwellers who have never heard a Petty tune, a quick march through the Greatest Hits album is still the way to go. For anybody else, An American Treasure is a total win. Its showcase of b-sides, leftovers, outtakes, and live performances keeps a tight focus on the fact that Petty left this world plenty of excellent material that went underappreciated while he was alive. Well, it’s time to dig into that. And for the fanatics of Tom Petty Nation, there are more than enough tiny slivers of nuanced change-ups to delight even the most expert geezer. This box set will hold up well as time continues to tick forward, with plenty of fresh meat on its comfortable old bones.

- Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers: Runnin' Down a Dream

- Tom Petty and The Heartbreakers: Hypnotic Eye

- Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers: Mojo

- Tom Petty: The Soundtrack of our Lives

- Tom Petty and George Harrison Were Two Sides of the Same ...

- The 20 Best Tom Petty Songs

- Tom Petty: Wildflowers & All the Rest | Music Review - PopMatters