Pixies frontman Charles Thompson (aka Black Francis) recently revealed the genesis of the many incendiary tracks on the band’s 1988 Surfer Rosa album, probably the most celebrated record to have come out of the whole alt-rock era. He claimed that his “most well-known songs come from something that just happened one day — you come up with a chord progression, you throw down a lyric and boom”.

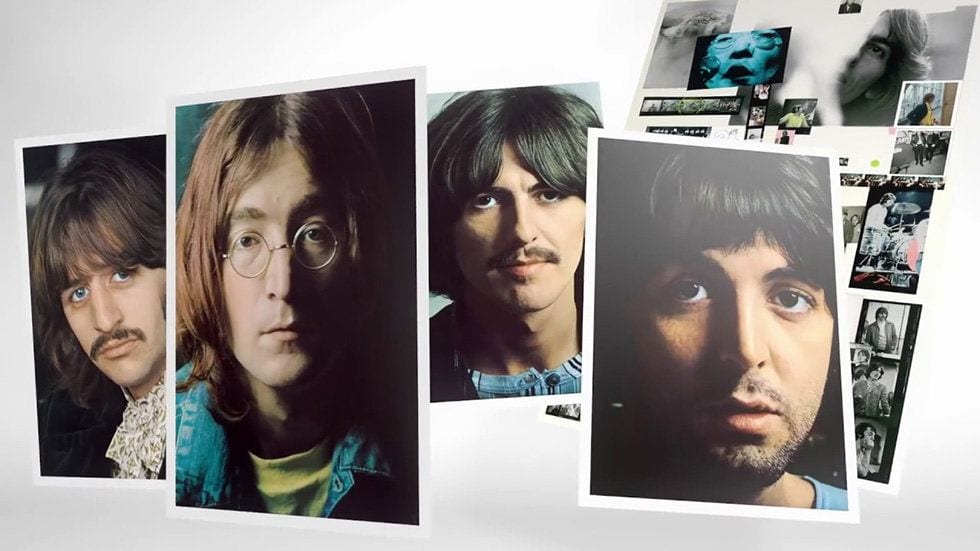

The track “Something Against You”, particularly, was recorded firmly in the tradition of the raucous burst of 12-bar blues to be found on side two of the Beatles‘ eponymously named double LP of 1968, universally known as the White Album: “[It’s] just a little riff, we played it fast in a punky way, I scream one line on one particular spot. It’s almost an instrumental, it’s minimalist, like the Beatles’ ‘Why Don’t We Do It in the Road?'” (Uncut, September 2018).

As proponents of raw, sparse, and semi-improvised rock, there can be no doubt of the Pixies’ considerable debt to the White Album, and its excursive revelry in rootsy musical styles. The band absorbed it into their sound, together with a healthy dose of hardcore punk and surf rock, to spark an alt-rock explosion that would last into the mid-1990s. This explosion saw a punk-infused cohort made up of Sonic Youth, the Breeders, Soundgarden, Pearl Jam, Nirvana, Pavement and the Smashing Pumpkins also buy into the White Album, in reaction against a posturing, poodle-haired, and power-ballad-obsessed rock establishment.

These groups exploited this legendary four-sided record to advance their subversive cause with hard-edged, do-it-yourself, and angst-ridden guitar noise, usually on an independent record label. It gave them license to make albums rammed with unrefined tracks in a jarring range of genres, free of a producer’s interference, and with the option of spending an inordinately long time in the studio.

The concern here is to spotlight the White Album as a precursor to what was essentially the last truly vital episode in rock, so it will be prudent to first clarify its status as an archetype of musical eclecticism. This will enable an assessment of the varied ways in which the protagonists of alt-rock, beginning with Hüsker Dü, emulated its 30-track, multi-stylistic sprawl, to the extent that Pearl Jam’s Eddie Vedder called it “almost a textbook for someone born in 1964” (Spin, December 2002). We’ll see from this that they drew not so much from the Beach Boys-flavored rock of “Back in the USSR” as the rather less commercial aspects of the record, in their bid to demonstrate authenticity and cathartic expression above all else.

This meant the brutally loud hard-rock of “Helter Skelter”, the folky brevity of “Wild Honey Pie”, the tooth-decay-themed soul of “Savoy Truffle”, and the sound-collage experimentation of “Revolution 9”. It also meant the three-part hybridity of “Happiness Is a Warm Gun”, and the satirical-yet-real British blues of “Yer Blues”, not forgetting the visceral rock of “I’m So Tired”, a track on which there is to be found a certain quiet-loud-quiet dynamic that somehow seems relevant.

The White Album became a model for the alt-rock movement upon being defined by its unprecedented display of divergent musical forms following its release on 22 November (in the UK) and 25 November (in the US) 1968. The New York Times noted its mix of “blues, country, easy listening, folk, and 1955-to-1962 rock”, but wasn’t entirely convinced by some of the styles: “There are a number of electronic distortions, and there are many put-ons” (November 1968). Time magazine commented, rather negatively, that it lacked “a sense of taste and purpose” (December 1968) and The Village Voice subsequently called it a “pastiche of musical exercises” (September 1971).

However, along the way, the multiplicity of its makeup has been deemed to constitute the template for any artist to have altered course repeatedly over the distance of an album without inviting accusations of self-indulgence. This is such that the terms “their White Album” or “your White Album” have become commonplace within rock discourse. Indeed, Pitchfork, recognizing this in its placement of the double LP at number four in its “200 Best Albums of the 1960s”, has stated that to “record your White Album is to make something that tugs and bursts at its own seams” (22 August 2017).

The Beatles can now be seen to have originated the White Album archetype out of marginalization of their paternalistic producer, George Martin, during the four-month, tour-free period of making the record. Biographer Kenneth Womack, for the second volume of his Sound Pictures (2018), has publicized new quotes as evidence of this from sound engineers present at the studio sessions in 1968, who claimed he was doing “nothing” for a lot of the time: “he was in the back of the booth, reading newspapers, sharing his chocolate with us”. Womack argues that this was the result of the band reacting against the elaborate and ornate Sgt Pepper-era studio creations he had taken credit for and which they now viewed as the epitome of an outmoded psychedelic sound (The Guardian, 18 August 2018).

The Beatles, therefore, created a model of live performance in the studio and making material up on the spot, regardless of an inclination to double-track their vocals as a way to smooth over imperfections. They made it a model of studio talk and off-the-cuff remarks infiltrating the music, stemming from the “two, three, four’s” on the LP, the “one more time”, the “ey up!” and most famously the “I’ve got blisters on my fingers!” They also made it a model of stripped-down instrumentation and a fluency in the way different personas are taken up to give a song a particular flavor, evident in John Lennon becoming a self-pitying blues singer on “Yer Blues” or a jilted lover (perhaps) on “Sexy Sadie”, or Paul McCartney becoming a storyteller of the Old West to sing “Rocky Raccoon”, which he does in a hammy Western drawl.

- The White Album: Side Three - PopMatters

- The Beatles: White Album - Side 2 - PopMatters

- Birthday: The White Album Turns 40 - PopMatters

- The White Album: Side One - PopMatters

- The Beatle's White Album

- The White Album: Side Three - PopMatters

- The White Album: Side Four - PopMatters

- Birthday: The Beatles' White Album 40th Anniversary

- Counterbalance No. 14: The Beatles' 'The Beatles' AKA "The White ...

- The Glorious, Quixotic Mess That Is the Beatles' 'White Album ...

- Riotous and Hushed: The Beatles' 'The White Album' - PopMatters

- Kristin Hersh Discusses Her Gutsy New Throwing Muses Album - PopMatters