Like everyone else, I listened to nothing but David Bowie in the days after hearing the news. The night Bowie died, I had felt a disturbance in the Force at 3:00 am, saw the news via text, got out of bed, bereft, and put on Station to Station, knowing that no way in hell I was getting back to sleep. When rock heroes die, it always hurts. But Bowie hurt more, for several reasons, among them that he wasn’t yet 70, that he was still creating so aggressively, and that we didn’t know he was sick. But beyond those earthbound concerns, there was just something about David Bowie that made him seem more immortal than everyone else. My initial reaction when I heard that he died was confused incredulity: “What do you mean, David Bowie died? David Bowie doesn’t die!“

At the time the news broke, I had spent the previous two days listening to Blackstar over and over. I had written something about the title song and its video for publication a few days earlier in which I mentioned how well Bowie was holding up, how intact his voice was, and how captivating a performer he remained. When his death was announced, I felt weird about those assessments, but it’s all true, even though he was days from death. Of course, now that we know that Bowie knew he was dying when he wrote the album, listening to Blackstar is a strikingly different experience.

Nearly 40 years earlier, Bowie hit my radar when I was too young to get it. I remember watching that Bing Crosby Christmas special the night it aired in 1977 and thinking that Bowie was a woman. Around 1980, I had gathered the nascent knowledge that rock and roll music is the most important thing in the world, by which time Bowie had been through a decade of shapeshifting that had made him the most influential rock figure of his era. For my generation, the entry point was Bowie as the lean, elegant, crooning statesmen of the New Romantics, the blonde lothario in double-breasted suits, all knees and elbows and quivering baritone, larger than life at Live Aid, where he debuted that “Dancing in the Streets” video with Mick Jagger, a bitchy rock god strut-off.

What was mistaken for sexual tension in the video was really just two attention-drenched singers at the height of their fame competing for the title of transcontinental king and queen of ’80s rock, and both Bowie and Jagger wanted both titles. It’s easy to argue that Mick wanted it more, that Bowie had a much different attitude about fame. Fame gave you no tomorrow, Bowie once sang. He was wrong about that, as it turns out, and Bowie was, in reality, acutely interested in the fluctuations in his commercial and critical successes. But it’s also true that, in many ways, Bowie often resided in a darker, more desperate place than Jagger. He came closer to falling apart, doubting his sanity, ravaged by cocaine, always preoccupied with death, alienation, by dystopias of all sorts.

Which is why Bowie was so important to his fans. Not because he was dark — or not solely because he was dark — but because within the darkness he also offered a sense of connection and liberation. Yes, you’re a rock and roll suicide, but “Oh no, love! You’re not alone!” You’ve got your head all tangled up, but no matter who you’ve been, there is the possibility of transformation from whatever prevailing norms of gender or class or popularity you’ve known. Hot tramps are everywhere; you can be like your dreams tonight. It was clear that one way or another, Bowie spoke to the entire world on non-squares. The glam kids, the punkers, the goths, the disco queens, the prog-rockers, the metalheads, the art-rock kooks, the stoners, the ladies, the gentlemen, the others: They all claimed Bowie as one of their own.

This transmutability was one of Bowie’s greatest gifts — he was impossible to box in or pin down, and as much as he turned to face the strange, he kept having hit after hit. Surely, no figure in rock history was able to reach such enormous commercial success through such a consistently challenging output of artistic boldness. Even when it came to Bowie’s musicality, he couldn’t be easily labeled. On one hand, just as Bowie told the tacky things that they looked divine, he was a hero to musicians who lacked conventional musical ability. Lou Reed, Patti Smith, Iggy Pop, the snarling punkers — they all loved Bowie because Bowie, too, found freedom in eccentricity and in not second-guessing himself based on popular or critical expectations.

Bowie himself was an unconventional musician: Detractors scoffed that he couldn’t sing properly and that “Ziggy” couldn’t actually play guitar after all. As a frontman, Bowie couldn’t move like Jagger or play like Springsteen. He wasn’t the perfect pop-song craftsman that McCartney was, and as a vocalist, he lacked the operatic range of Freddie Mercury or the full-throttled power of Robert Plant. And yet Bowie had more musical range than them all. He was an incredible writer of gorgeous melodies and brilliantly crafted lyrics, all the more genius for their bucking of easy structures and progressions. He was a remarkable singer with an array of voices — the brooding baritone, the vibrato-drenched croon, the baby-doll tenor, the nasal Englishman squawk, the yearning soul cry, the dancing falsetto — and every vocal break and wobble was artfully, intuitively placed.

Do you want musical alacrity in the studio? Bowie produced the Stooges’ Raw Power, Lou Reed’s Transformer (“Walk on the Wild Side,” “Satellite of Love”), Mott the Hoople’s All the Young Dudes (and wrote the title hit), and his own Ziggy Stardust album all in the same year. Bowie composed songs like a mad scientist, favoring complex progressions combining chords from different keys and turning it all into something startling and beautiful. Bowie was not only one of the great rock-guitar cultivators of all time, mentoring a steady stream of left-field six-string heroes, but he was also himself responsible for some of the most indelible guitar riffs, saxophone rides, and electronic tapestries on his records as a multi-instrumentalist and arranger.

This diversity and complexity are what made Bowie the ultimate rock star. He was at turns unrefined and a perfectionist. He dismissed fame and flamboyantly enjoyed adoration. He was a studio obsessive who staged giant visual spectacles. He could be musically and vocally rough around the edges and elegantly complex. Sometimes he looked bizarre — made of wax and with British orthodontia — but grew increasingly handsome and always indelibly cool. He was, at turns, a trailblazer and a classicist. And, yes, he was an even split between swishing femininity and masculine force.

Still, for all of the imagery that dominated the religiosity of Bowie — the fashion, the characters, the hairstyles — what matters most are the songs, and Bowie’s disciplined artistic drive and triumphant prolificacy as a songwriter have few peers. Yes, he’s championed for pushing ahead, for his willingness to be challenging, for having side two be nothing but ambient instrumentals, and for being strenuously experimental in form and sound. But the songs had to be great. Oddly, people don’t tend to mention Bowie when they rattle off that top tier of the Great Songwriters, but the Bowie catalog is deep and wide with astounding material, well beyond the hits. Here are 25 killer deep-track Bowie originals, album by album.

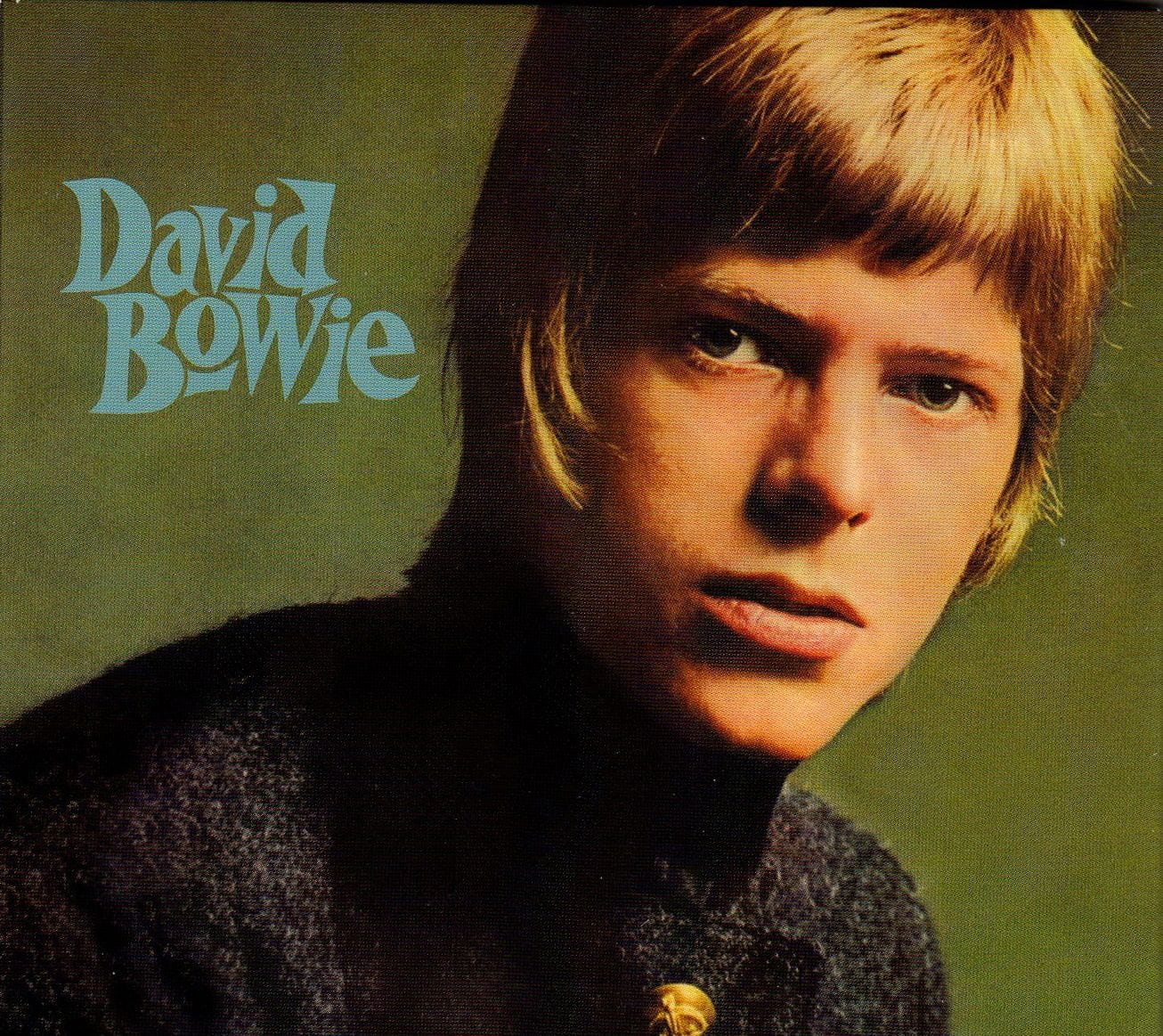

“Love You Till Tuesday” – David Bowie (1967)

The cockney-style music-hall ballads full of ye olde Englishisms were never a great fit for Bowie, even though his self-titled debut contains some real weirdness like the cannibalism tune “We Are Hungry Men” and the grim Dickensian character sketch “Please Mr. Gravedigger”. The best traditional pop number here is “Love You Till Tuesday”, opening like a game-show theme and giving way to Victorian Fauntleroy lyrics so ridiculous (“Who’s that hiding in the apple tree / Clinging to a branch? / Don’t be afraid it’s only me / Hoping for a little romance”) that Bowie himself couldn’t stifle a laugh. The super-catchy songwriting is no joke; however, a reminder that Bowie was the most sincere ironist in rock and roll.

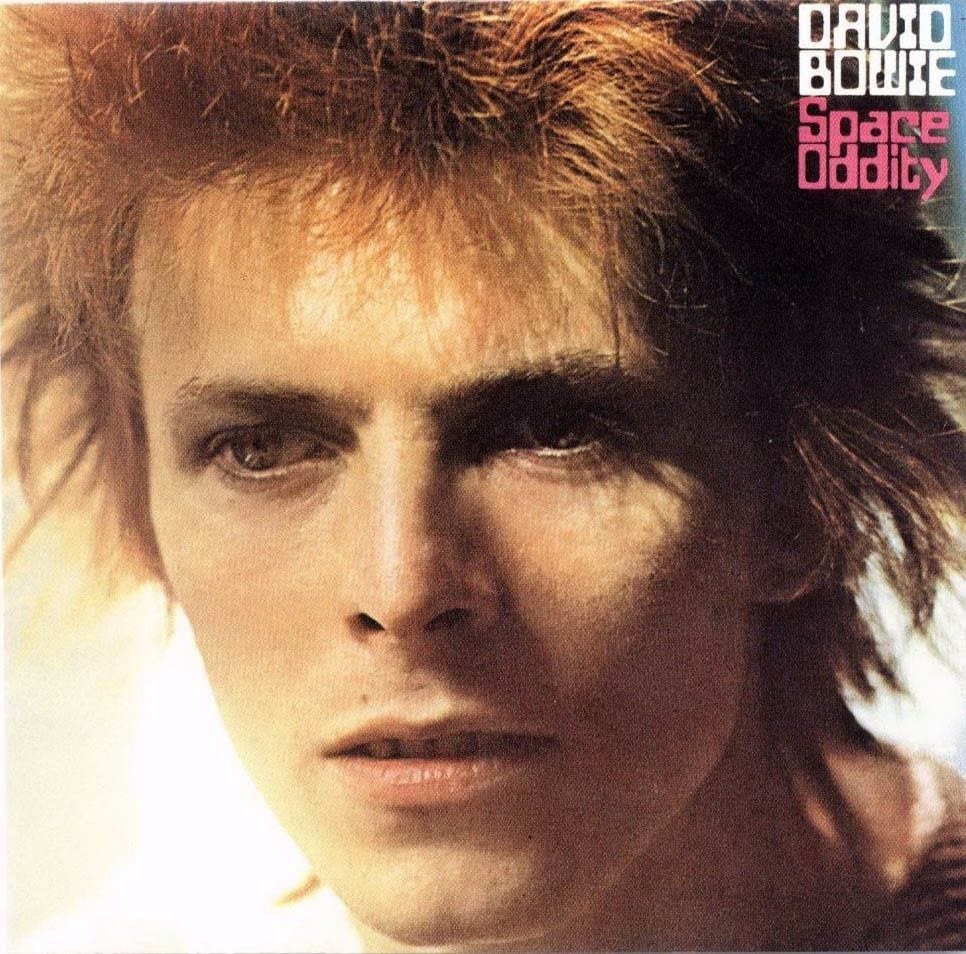

“Cygnet Committee” – Space Oddity (1969)

The title cut was the smash, but the oddly titled “Cygnet Committee” was where Bowie first demonstrated that he was capable of writing an epic and of working well beyond his years. In the song, Bowie rails gloriously against the empty promises of movements all around him, whether it’s the pretenders with whom he’s lost faith or rock platitudes like “love is all we need” and “kick out the jams.” Whatever the targets of Bowie’s apparent disappointment he turns into major affirmations of righteous selfhood in this stunning, moving masterwork of shifting narrative voices and melodic structures.

At a prog-mented nine-and-a-half minutes, “Cygnet Committee” gradually builds through a rolling series of song fragments, culminating in a long, rambling, passionate final section, with Bowie sounding like Jean Valjean fending off punching tremolo guitars and declaring his opposition to… well, it’s not entirely clear, but he emotes like his soul is at stake. “I want to believe!” and “I want to live!” he sings, a 22-year-old offering an early manifesto on a grand scale.

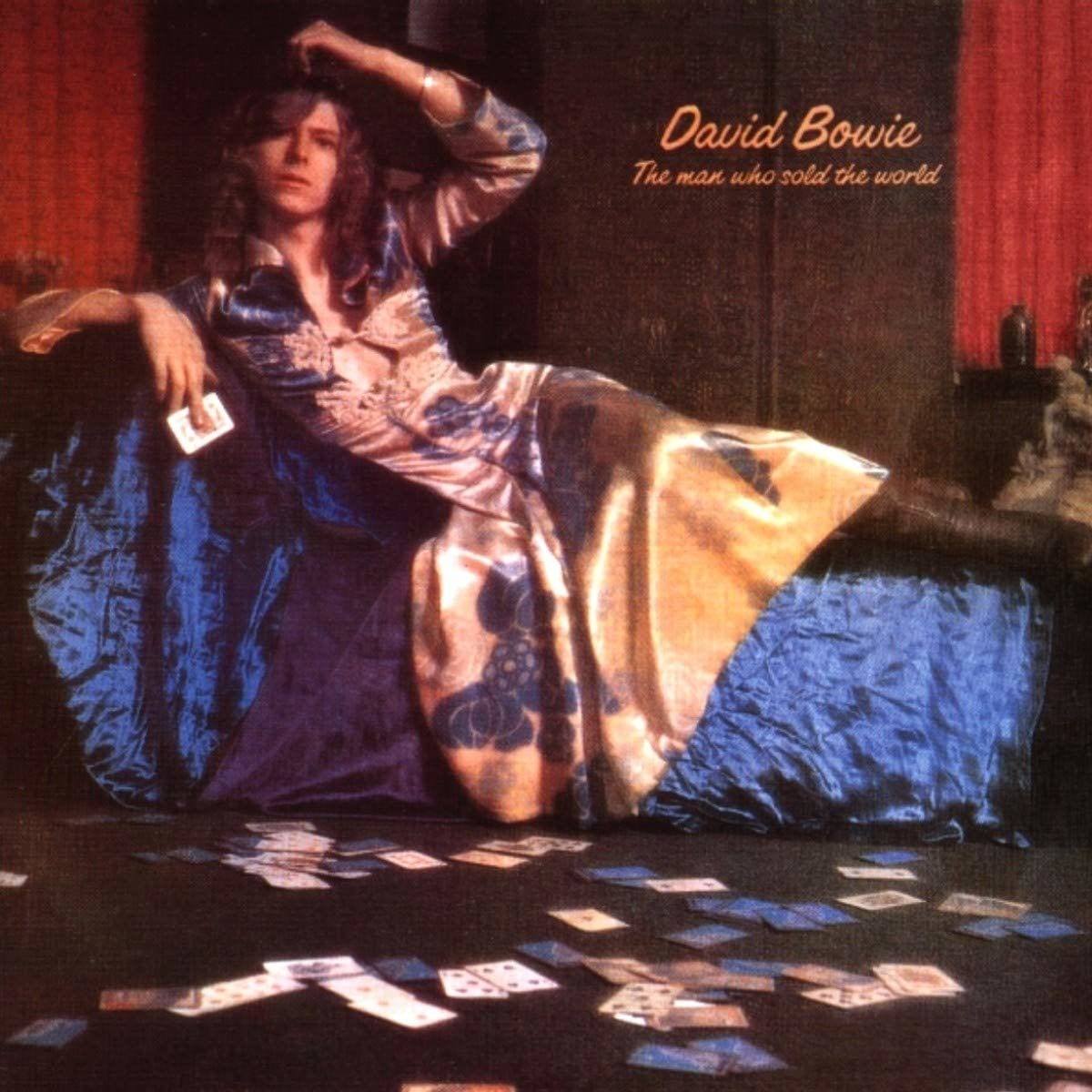

“The Width of a Circle” – The Man Who Sold the World (1970)

Bowie ventured into hard rock on The Man Who Sold the World, his third album of strikingly different styles in as many tries. “The Width of a Circle” is one that metalheads could get behind, a song that piledrives with the heavy guitar riffage and wailing vocals of Black Sabbath in the same fall that Sabbath’s Paranoid was released. Bowie’s first great guitar foil Mick Ronson has arrived, and he lays down some seriously wammy-drunk breaks over producer Tony Visconti’s busy, burping bass lines. Halfway through, the song shifts into a scary heavy blues chug as Bowie, already the cracked actor seems to describe a ménage à trois among himself, God, and the Devil: “His nebulous body swayed above/His tongue swollen with devil’s love/The snake and I/a venom high/I said, “Do it again, do it again!” Modern love gets him to the church on time.

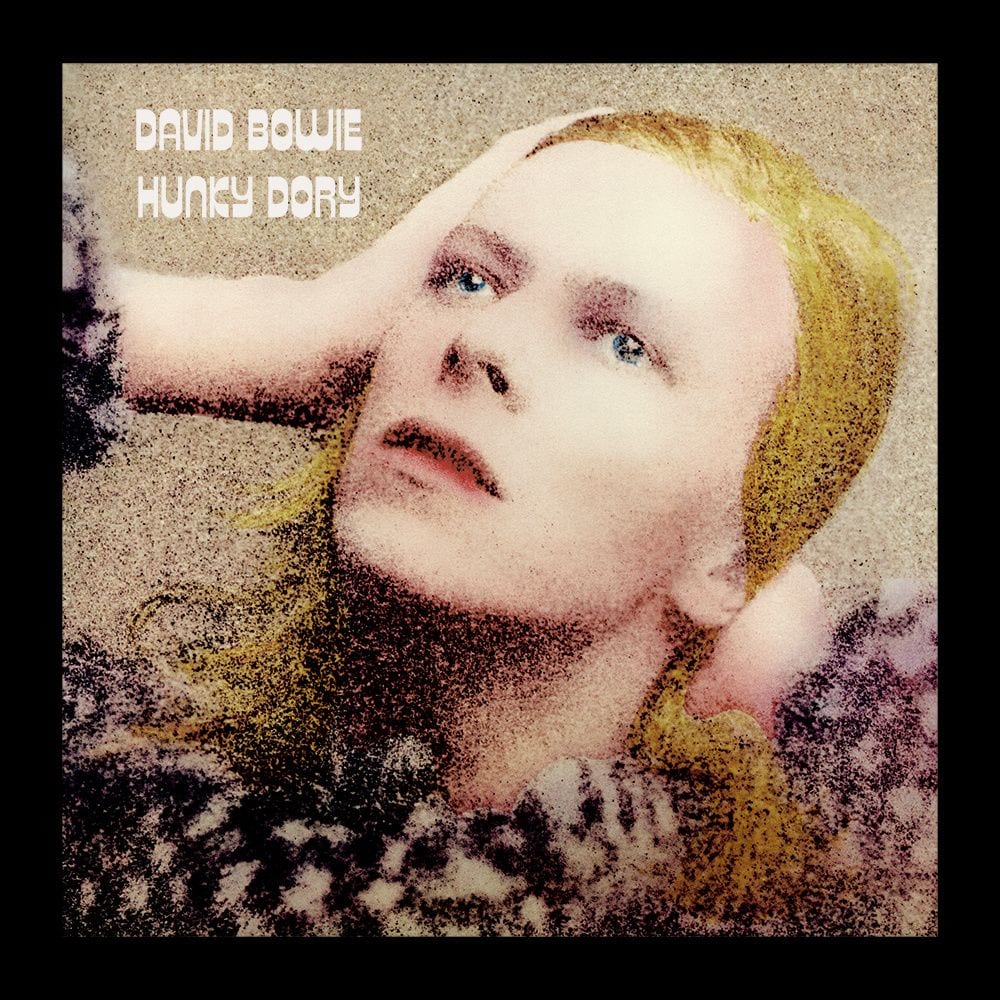

“Quicksand” – Hunky Dory (1971)

From Bowie’s first stone-cold classic, Hunky Dory comes this rambling, lilting expression of existential agony. You can hear the Beatles’ influence all over it, and John Lennon’s “Imagine” would be released just four months later. But instead of “Imagine there’s no heaven”, the 24-year-old Bowie offers a much bleaker assessment of the plight of man’s spiritual uncertainty: “I’m tethered to the logic of Homo Sapien / Can’t take my eyes from the great salvation of bullshit faith.” Over Mick Ronson’s stacked acoustic guitars (and gorgeous string arrangements) and future prog hero Rick Wakeman’s piano, Bowie delivers a weary-sounding summation to our deepest questions: “Knowledge comes with death’s release”, a line that in 2016 resonates like never before.

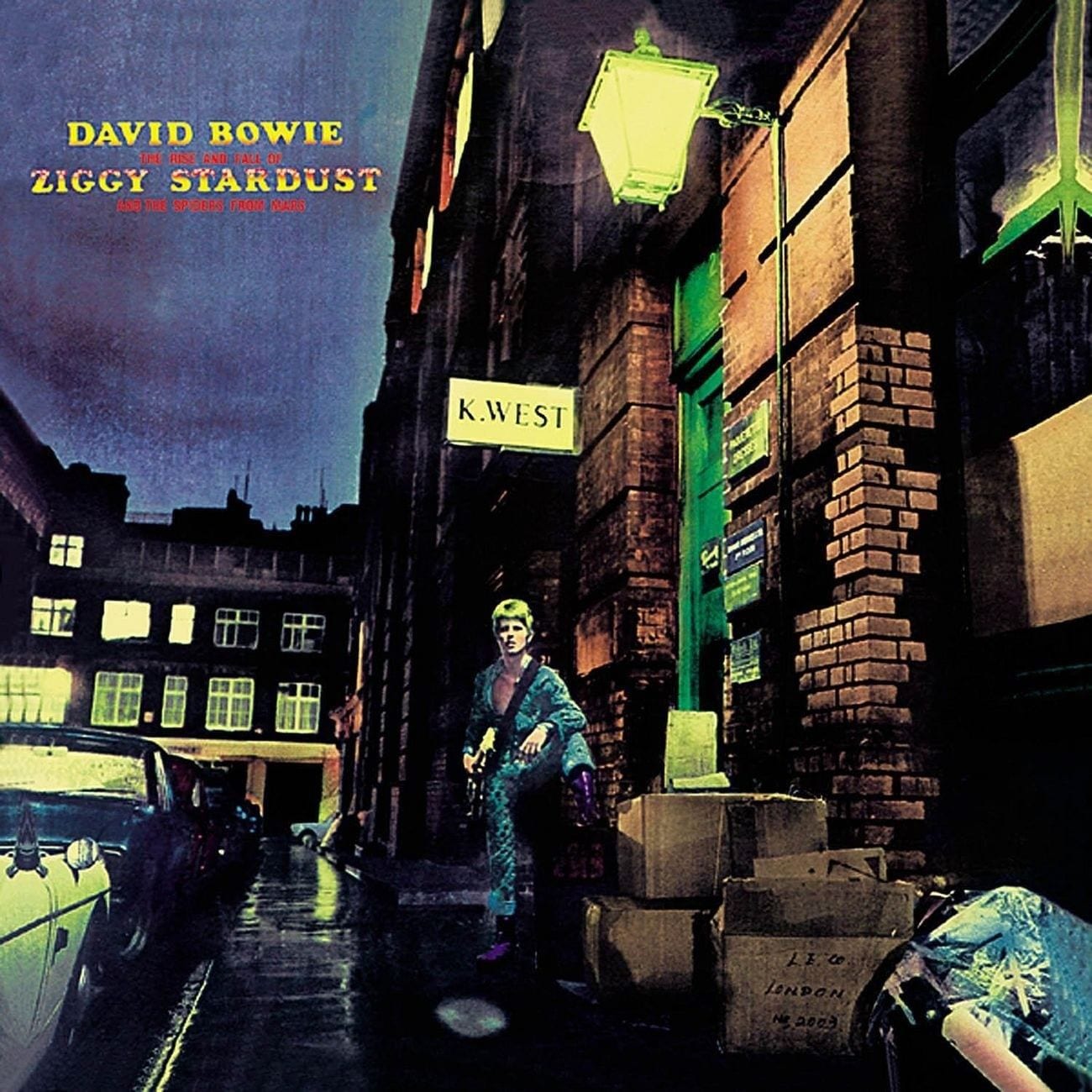

“Soul Love” – The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars (1972)

There is no “deep cut” on Ziggy Stardust, really, as anyone with more than a passing interest in Bowie is already intimate with the whole album. The second track, “Soul Love”, though, is a particular slice of Bowie genius. Opening with Mick Woodmansey’s slow-funk drums, Bowie sings over his own acoustic strumming and percolating saxophone before the song builds into a second section that reads like Shakespearean verse. Bowie combines sweet verses with a sour chorus in line with the double-edged sword in the song’s title, love that leads to both elation and pain (“a love so strong it tears their hearts…”). It all goes down easy as Bowie plays a hazy sax solo — two actually, one in each ear — and Mick Ronson’s guitar mimics the vocal melody during the coda, a gentle ending to one of Bowie’s prettiest odes to sadness.

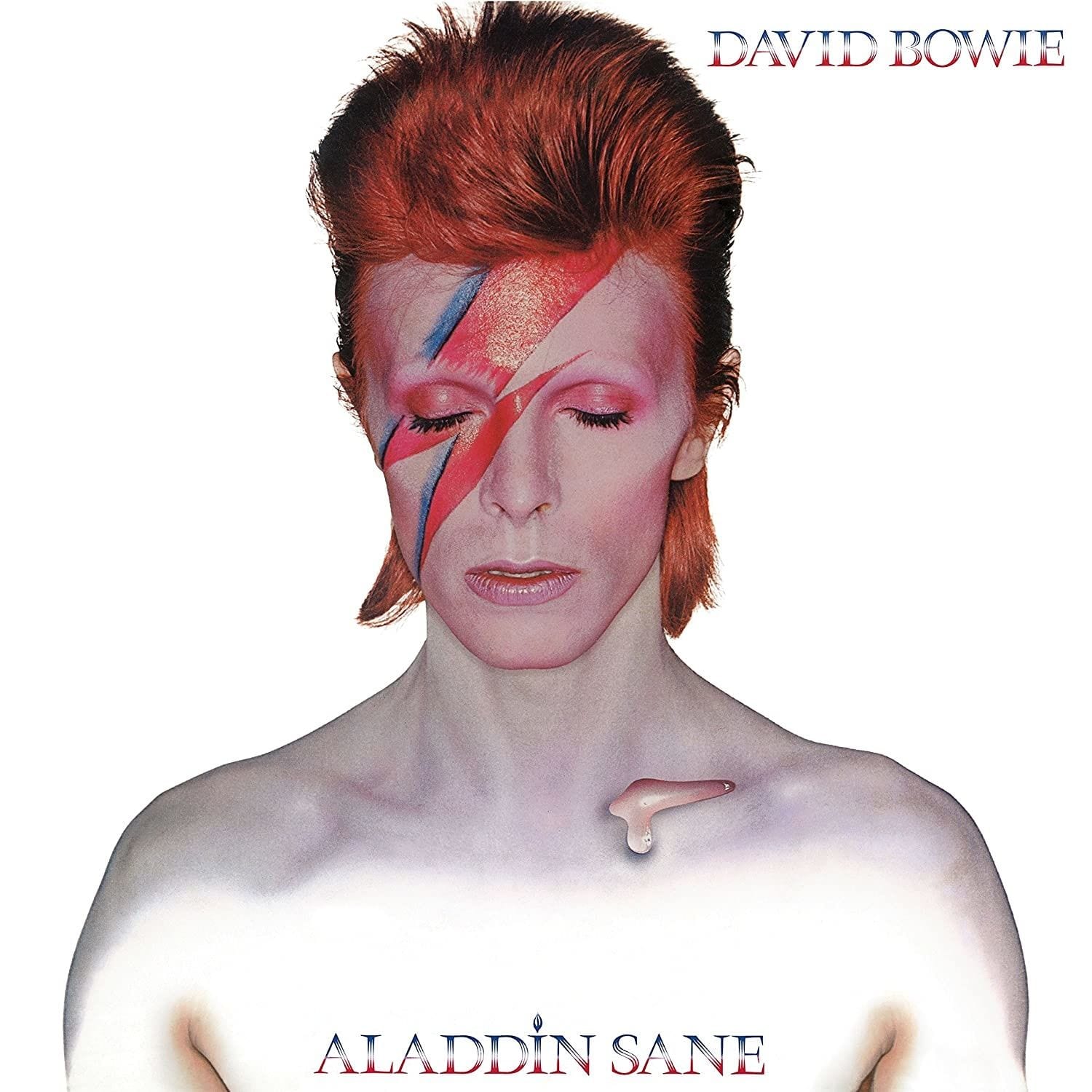

“Watch That Man” – Aladdin Sane (1973)

Aladdin Sane, a lad on cocaine. By now a major star in England, Bowie opens the album with a new look and sound (again), this time Bowie’s take on the Stones, a year after Exile on Main Street. Bowie rips the joint with his toughest vocals, buried within Mick Ronson’s ragged guitars, as Bowie describes some all-night drunken party in New York full of crooked society types and broken coke mirrors and sax and piano and backup singers all over the place. As the night goes on, things get more confused — “a lemon in a bag played the Tiger Rag” (a reference to Lennon’s bagism?) — and more paranoid until Bowie, “shaking like a leaf”, runs out of the party. That’s Mike Garson on a piano in Nicky Hopkins mode, kicking off a 30-year partnership with Bowie and trying to keep up with Mick Woodmansey, who plays the drums on this track like his hair is on fire.

- David Bowie: Young Americans

- David Bowie: The Next Day

- David Bowie: The Buddha of Suburbia

- The Great I Am: Magic, Fascism, and Race in David Bowie's 'Blackstar'

- Counterbalance No. 16: David Bowie - 'The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars'

- David Bowie: ChangesNowBowie

- 'What a Fantastic Death Abyss': David Bowie's 'Outside' at 25